[25-Minute Deep Dive] The Preachers Who Bought Slaves with the Bible in Hand—Now Finally on Exhibit!

![[25-Minute Deep Dive] The Preachers Who Bought Slaves with the Bible in Hand—Now Finally on Exhibit!](/content/images/size/w960/2025/05/DO01123269.jpeg)

01

Foreword (Second Attempt) – May 24, 2024

Opening my drafts folder, I came across an unfinished piece. It began in September 2024, shortly after I visited the exhibition Christianity and Slavery at the Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht. The experience moved me deeply, and I felt compelled to write something. But the essay was soon swept away by the demands of my daily reality—promoting cocktails, visiting liquor stores, and cycling long distances across the Netherlands. It remained untouched.

Even now, I believe that exhibition deserves to be taken seriously—especially by Dutch society today. It wasn’t an attempt to whitewash the past, but rather a beam of light drawn from faith and reflection, shining into the darkest corners of the Netherlands’ colonial legacy.

What I gained from the exhibition went far beyond historical facts. It taught me a kind of spiritual courage. In various settings, I have shared what I saw there with Dutch friends, encouraging them to look at the VOC (Dutch East India Company) through a different lens—not to demonize or romanticize it, but to understand the moral tension of that era with both responsibility and compassion.

I was particularly moved by the stories of pastors who chose to “buy” enslaved Africans—not because they approved of slavery, but because they wanted to rescue these individuals from abuse, to give them protection, dignity, and access to the Gospel. It was a form of moral action we rarely grasp today—a wisdom of love expressed through pragmatic sacrifice.

I often find myself resisting a popular misconception: that the abolition of slavery came solely through bottom-up violent revolution, as if justice in history can only be ignited by rage. But this exhibition revealed a more complex truth. True emancipation emerged from the difficult, years-long cooperation between anti-slavery Christian communities, principled politicians and merchants, and the early free Black population. It was not an explosive overthrow—it was a dismantling by grace, the slow fruit of faith, organization, and moral persistence.

Many Dutch people may not understand why I hold this exhibition in such high regard. But if they could see the “taboos” I live with—the things that cannot be spoken aloud in my own culture—they might begin to understand. For me, this exhibition was a moment of light piercing through the moral valley of humanity. It was the first time I truly saw, on this soil, a glimpse of repentance and renewal.

02

Foreword (First Attempt)

Between Faith and Suffering: Reflections on Three Visits to Christianity and Slavery

At the heart of Utrecht, the Museum Catharijneconvent recently concluded a three-month exhibition titled Christianity and Slavery. I had the privilege of visiting it not once, but three times—thanks to the fact that I live in this very city.

The first visit, I went alone, bringing with me a heart full of skepticism and critique.

The second, I invited a friend who was studying photography in London.

The third, I brought my nephew—who had just been accepted to Leiden University—along with his parents.

As someone raised and educated in China, I’ve long felt a deep anger and distrust toward the European colonial slave trade. When I first stepped into the exhibition, I confess I was wearing ideological lenses. I wanted to see: how would Europeans today speak of their colonial past? Would they still cloak historical violence in the language of “civilization”?

Slavery, after all, is a chapter of human history written in dark tones—shadows of suffering, weight, pain, and despair. We are used to interpreting it through the dual lens of guilt and punishment, blood and injustice. But this time, I was seeking something more: How did the Christian world understand slavery in its own time? What role did the Christian faith play in either the justification or the dismantling of the institution? And what kind of theological legacy did it leave in the struggle toward abolition?

I must admit: the exhibition exceeded my expectations.

To begin with, the curators and contributors displayed a depth of sincerity and courage. They did not attempt to paint over the shadows of history with the bright colors of Western progress. They resisted the temptation to glorify “civilization” and instead unveiled—delicately but truthfully—the complex roles played by churches, merchants, and political systems. Among them were perpetrators, bystanders, and prophetic voices who dared to speak out in the darkness.

I learned that during the height of the slave trade, not everyone went along with the tide. There were clergy, reform-minded Christians, and a few morally awakened businessmen who stood their ground—some even attempting to purchase enslaved individuals to offer them a better fate. Though marginal at the time, such actions were like flickers of light along a long night, leaving behind a moral imprint that would guide future generations.

Through this exhibition, I also gained a renewed respect for one particular strength in European civilization: the capacity for reflection.

What enables Europe to move forward is not the absence of historical error, but the presence of historical repentance. It is this self-critique that becomes the seedbed for genuine progress. That, for me, was the exhibition’s deepest message: that justice should not merely be the victorious end of a struggle, but the humble beginning of repentance.

Then, turning my thoughts back to my own homeland, I fell into a silence I know too well.

Rarely do I encounter spaces in which the gray zones of Chinese history are examined with such honesty. It is not that I’m unwilling—but rather that I often lack access. In our cultural and social context, the very act of “reflection” is still met with quiet resistance.

And so, for me, this exhibition was not just about slavery.

It was about witnessing how a nation can use culture to ignite the fire of repentance—and pass that fire on to the next generation.

In today’s globalized and pluralistic world, such efforts are not only commendable.

They are essential.

03

Prologue: Between Light and Shadow — A Gaze into Faith and Enslavement

The special exhibition Christendom & Slavernij (Christianity and Slavery), held at the Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, concluded in the autumn of 2024. Though it lasted for only three months, the tremors it stirred within me defy such temporal boundaries.

As an observer from China who has lived in Europe for many years, I visited the exhibition three times. The first time, I went alone, carrying a heart full of caution and skepticism. The second time, I was accompanied by a friend studying photography in London. The third time, I brought along my nephew—newly admitted to Leiden University—and his parents. Though the physical path through the exhibition remained the same, each visit brought a deeper, more contemplative emotional journey.

I entered the exhibition with one piercing question in mind:

“Can a Christian be a slave owner?”

This was not only a thematic undercurrent of the exhibit—it is a question that has haunted the theological, political, and economic foundations of the Dutch colonial system since the 17th century.

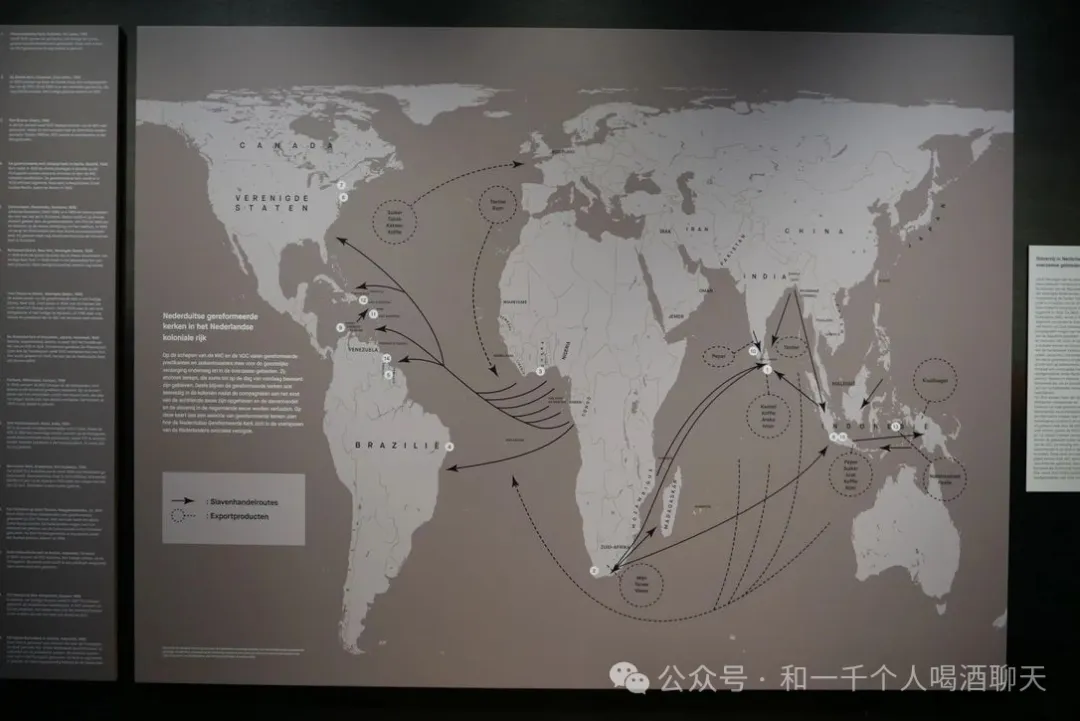

The exhibition offered no emotional sensationalism. Instead, it presented a calm, rigorous structural analysis: under the dominance of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the West India Company (WIC), slavery became a foundational pillar of colonial economic life. More than 1.8 million Africans and Asians were enslaved, traded, and transported. During this same period, the Dutch Reformed Church—then the public church of the Republic—at times collaborated with colonial authorities, jointly shaping the religious “legitimacy” of empire in the colonies.

Yet this was no binary portrayal of good versus evil. The exhibition also gave voice to the dissenters—pastors who risked disgrace or excommunication to speak out, clergy who sought to buy enslaved individuals from their masters in order to grant them freedom, and preachers who proclaimed dignity in the name of the Gospel. These were not victors of history, but in the pitch darkness of humanity’s moral failure, they lit candles of faith.

The curators also exercised care in their use of language. Instead of “slaves,” the term enslaved persons was used throughout—an intentional linguistic act that restores dignity and rejects the fatalism of identity-as-destiny.

To me, this was not simply an exhibition about slavery. It was a mirror—reflecting how a nation dares to confront the shadows of its past through collective memory, seeking responses and repair through faith, art, and historical reflection. This honest effort reassured me that what makes European civilization commendable is not an absence of guilt, but a willingness to confess wrong and attempt repentance through culture.

This is the origin of these words.

It is a gaze stretched across three centuries of colonial history.

And it is a question—of soul, of responsibility, of hope.

04

Part One: The Republic (1588–1795) — A Puritan Nation

The Dutch Republic once fashioned itself as a land of liberty. Around the year 1600, this Protestant state had no legal framework for slavery within its domestic borders. Every person on Dutch soil was either born free or became free upon arrival. In contrast, the Spanish and Portuguese colonies remained steeped in slavery, and Dutch Calvinists scorned such practices—often equating slavery with “non-Christians” (niet christelyck) and attributing it to the moral decay of Catholic tradition.

And yet, this ideal of no slavery on Dutch soil did not extend to the overseas territories. Under Dutch colonial rule in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, slavery was quickly institutionalized as an economic necessity. Profit-driven trading companies such as the VOC and WIC integrated enslaved labor into the machinery of global commerce, gradually legitimizing the practice. More troubling still was this: faith did not function as a barrier to this system—it was quietly folded into it.

Consider the case from 1596, when a Dutch merchant ship accidentally docked in the port of Middelburg with 130 enslaved Africans on board. The then-mayor, Ten Haeff, argued that since these individuals had received Christian baptism, they should now be free: “They are no longer pagans.” He even proposed they be given religious instruction, vocational training, and pathways for social integration. But the Dutch States-General declined to take a clear position. Their response was vague, ambivalent—you may do what you will, but do not expect our endorsement.

This chapter of the exhibition exposed a profound historical paradox:

At home, Christianity was a symbol of freedom.

Abroad, it became an ethical fig leaf for oppression.

As the Republic’s “civil religion,” the Dutch Reformed Church remained largely silent on moral grounds. Worse, it actively collaborated with the colonial administration in determining which denominations could “spread the Gospel” in the colonies. Thus emerged a system of double standards: in the Republic, Christian identity protected individuals from slavery; in the colonies, Christian identity did not protect enslaved persons from bondage. In fact, some pastors and clergy members were major shareholders in the slave trading companies themselves.

This is a deeply unsettling mirror:

The Gospel sailed aboard the same ships as the whip;

Psalms were sung alongside the clinking of shackles.

History did not remain silent. It speaks—through ship manifests, through pre-departure prayers, through ledgers of human cargo—and it asks a piercing question:

When profit is pursued in the name of Christ, what remains of faith’s integrity?

05

Part Two: Holding the Bible in Hand

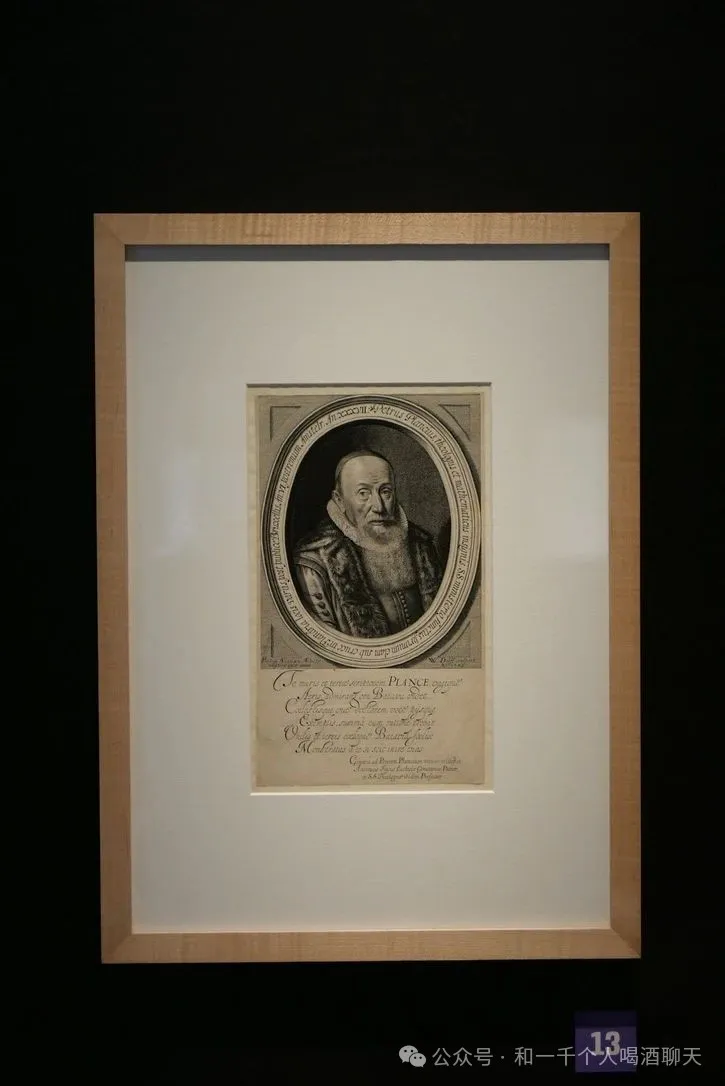

Petrus Plancius (1552–1622), known as the Father of the Protestant Mission.

A co-founder of the VOC and a figure associated with the WIC.

In all his surviving writings and letters, there is no indication that he ever declared anyone to be born to be enslaved.

When Faith Becomes Entangled with Slavery

We often associate the Bible with liberty, love, and justice. But in the historical context of the Dutch colonial empire, this sacred book became both a weapon and a shield.

From the 17th to the 19th century, Dutch Protestant pastors and theologians stood on both sides of the slavery question. Some defended the institution, while others lifted the banner of Scripture to denounce its evil. Seen from today’s vantage point, they stood under the same faith yet gave radically different interpretations of bondage and freedom. The second part of the exhibition painted a vivid portrait of this internal conflict—a kind of civil war within faith itself.

Those Who Used the Bible to Defend Slavery

They cited the Book of Genesis, where Noah curses Ham’s descendants—specifically Canaan—to servitude, interpreting this as divine justification for the enslavement of Black people. In their theological frameworks, slavery was not an affront to human dignity, but a fulfillment of divine order. Africans were labeled “sons of Ham,” and this theological labeling served to reinforce racial hierarchies and societal stratification.

Scholars have noted that early colonial expeditions often included Bibles, hymnals, and scheduled prayers or Sunday worship services on board. In some synod records, pastors seriously debated questions such as: “Must a slave be baptized before they can be freely traded?” These men were not atheists—they believed in God, but in a God who permitted inequality to persist.

Those Who Raised the Bible to Oppose Slavery

And yet, it was also those holding the Bible who became some of the earliest voices against slavery.

The exhibition featured figures like Engelbertus Matthias Engelberts, who in the 18th century bitterly exclaimed, “The coffee in your cup is brewed with the sweat and blood of slaves.” It included Jacobus Capitein, a Ghanaian-born pastor trained in the Netherlands, who held a complex stance on slavery but still fought for the spiritual freedom of Africans.

Most touching of all were the largely nameless missionaries and ordinary citizens—those who left no legacy in seminaries but wrote letters to authorities, pleading for enslaved African children to be seen as capable of learning, of believing, and of growing into faithful Christians.

The Bible as a Mirror with Many Reflections

Does the Bible support slavery?

This is not a question with an easy answer.

As the exhibition so clearly demonstrated, the Bible was not the source of slavery—but it was employed by people on both sides of the divide to justify the positions they already held. Some wielded it to preserve oppression. Others, to stir resistance.

And this is the value of the exhibition’s second section:

It offers not conclusions, but tensions.

Not simplifications, but the full weight of theological, moral, and colonial entanglement.

The same pastors who wrote hymns into their ship logs also recorded chains, plagues, and death.

Faith, in this setting, could both illuminate the soul—and cast a long shadow.

Closing Reflection: Faith Was Never Meant to Be Private

When religious belief becomes embedded in the structures of empire, it ceases to be a purely private matter.

It shapes the worldview of the colonizer, and it deeply marks the dignity of the enslaved.

This section reminds us: to reflect on our faith is not to betray it—but to return it to its truest origin.

06

Part Three: Church, Merchant, Pastor — The Alliance of the Sacred and the Secular

In the Dutch Republic, religion, commerce, and colonial governance were not distinct spheres of power. Rather, they formed an intricate web—mutually entangled, mutually reinforcing—woven together by the threads of “divine providence and commercial rationality.” Within this web, many pastors, elders, and church delegates became, directly or indirectly, beneficiaries of the slave economy.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the West India Company (WIC) not only hired pastors to sail aboard their ships, but also permitted them to establish churches in colonial territories. The pastors’ salaries, more often than not, were drawn from profits generated by enslaved labor. In Paramaribo, for instance, crops like sugarcane, cocoa, and cotton—harvested on “church lands” (kerkgrond) cultivated by enslaved people—were used to sustain the local church system. Some pastors even invested personally in plantations or slave trading companies, thus assuming a dual identity: minister of the Gospel and capitalist entrepreneur.

Ironically, a slave’s attendance at church was regarded as the master’s “spiritual duty.” In the Lutheran church of Batavia (present-day Jakarta), enslaved persons were marched in at their masters’ command, standing quietly in corners, galleries, or even on the floor during the sermon. This act was framed as salvific, but in truth functioned as a ritual that reinforced social hierarchy and colonial control. Many were baptized, given Christian names—yet never granted true freedom.

Though the structures and scale of slavery varied across the Dutch colonies in the East and West, they shared a common theological distortion: the conflation of spiritual salvation with social subjugation. Baptism did not entail emancipation. “Spiritual liberty” often served to conceal the reality of bodily enslavement. The missionary Brandes once said: “The African girl Betja was a playmate of my son”—yet when she fell in love without permission, he had her whipped, shackled, and sold. He drew her portrait with affection—then commodified her body.

Perhaps most jarring is the story of Pastor Basseliers, the first Reformed minister stationed in Suriname. He not only led a congregation but also founded a private plantation and imported slaves from Africa aboard the ship De Oranje (“The Orange”). A shipping manifest from 1683 records that he purchased “goods” in exchange for 80 pounds of sugar—those “goods” included eight African persons aged 12 and up.

These pastors were not demons. They were real people.

Their choices—made at the crossroads of spiritual mission and economic pressure—embodied the core contradiction of the colonial Dutch society: a nation that believed in God, and in profit.

Behind it all, slavery functioned as a hidden pillar of the Dutch Christian socioeconomic order. The Church was not merely a witness—it was a partner. Pastors preached the Word and purchased lives. The pulpit proclaimed grace, while also—through its silence—legitimized exploitation.

This marriage between Church and slavery was not just a moral contradiction.

It was a historical wound.

Through this part of the exhibition, we are forced to reckon not only with how sacred office was co-opted by profit, but also to ask:

Have we, today, inherited a faith structure that appears bright—yet conceals injustice beneath its foundations?

07

Part Four: Conversion Without Freedom

What did it mean to convert to Christianity under the shadow of slavery? It was more than a transformation of the soul—it was a theological battleground embedded in structures of power.

In the Dutch Republic and its colonial territories, the dominant theological stance at first was this: a true Christian should not be a slave. As a result, many slaveowners feared that once enslaved individuals were baptized, they would be obligated to grant them freedom. This belief created a major deterrent to missionary work among enslaved populations.

By the mid-18th century, however, a new theological trend began to emerge—one that fully separated spiritual freedom from bodily freedom. According to this view, Christian liberty meant “freedom from sin,” not freedom from slavery. Under this framework, missionaries were permitted to work within plantations, so long as their focus remained on salvation of the soul, not emancipation of the body. Slaveholders, now reassured, no longer saw baptism as a threat to their property.

Various synods even moved to narrowly define who could be baptized. The Synod of Dordrecht in 1618, for instance, stipulated that the children of pagans could only be baptized after proper instruction. Yet in the colonial context, such rules often became tools of exclusion—reinforcing a hierarchy of faith that mirrored the hierarchy of race and power. By the late 18th century, in places like Suriname, a few pastors within the Reformed Church—such as Jan Willem Kals—began to question the moral decay of these practices. He publicly denounced the absurdity of “nominal Christians” coexisting with slavery. For this, he was expelled from the colony.

The Moravian Church stood as a notable exception. Known for their evangelistic fervor, the Moravians focused intentionally on ministry to enslaved communities. In places like Suriname and the Danish West Indies, they sought to form genuine spiritual communities with the enslaved—marked by mutual recognition and shared worship. Many converts adopted new names, new clothing, and new faith identities. Some even relocated to Herrnhut, Germany, seeking a fuller spiritual life. These conversions became more than inward confessions—they were acts of cultural transformation.

One document in the exhibition was particularly striking: the 1794 baptismal record of Maria Zara Johanna Niabi, a girl sold into slavery from West Africa, who was later baptized in the church of Delft. The baptismal text cited Ephesians: “You were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord.” This declaration of spiritual rebirth also carried layered cultural undertones, in a society where “light” and “darkness” were not merely metaphors, but instruments of social division.

These artifacts remind us:

Religious conversion under slavery was seldom a matter of pure, uncoerced choice.

It was a journey woven through oppression and grace, possibility and distortion.

It could offer hope—Or become a new form of spiritual bondage.

08

Part Five: The Road to Abolition

The abolition of slavery in the Netherlands was not a swift or linear process. It unfolded gradually, fraught with contradictions and tensions between competing forces. Within this complex journey, religion played a dual role—both as a delayer and as a liberator. Especially from the mid-19th century onward, growing ethical unease among segments of the Christian community began to echo the waves of the British abolitionist movement, catalyzing shifts in Dutch theological thinking.

From Spiritual Freedom to Physical Liberation

In the early 19th century, churches such as the Moravians, the Roman Catholics, and the Dutch Reformed Church began to engage in social reform through education and healthcare, often framed as ways to “improve” the enslaved population. Colonial authorities permitted the establishment of schools and hospitals on plantations, viewing Christianization as part of a broader civilizing mission. In Suriname, compulsory education was introduced as early as 1876—preceding its implementation in the Netherlands—signaling a new stage of interaction between Christian missions and emancipation.

However, these “progressive” measures were often laced with paternalism. Alongside literacy and religious instruction, missionaries instilled a rhetoric of obedience and docility. As missionary Otto Tank once wrote, “A slave who is well treated will behave more virtuously.” Such “civilizing discourses” were frequently used to morally soften the brutality of slavery.

Mission Work and Linguistic Liberation

Translation of the Bible became one of the most profound cultural pathways toward emancipation. Martinus Niewindt advocated for translating religious texts into Papiamentu, the local creole language of the Dutch Caribbean. The Moravian Church went even further, publishing illustrated Bible stories in local languages for enslaved people as early as 1852. This localized expression of faith not only supported the spread of Christianity—it also empowered enslaved communities to reclaim a sense of self through language and literacy.

Dissent and Resistance

More and more pastors and church members began to question the morality of slavery. Peerke Donders, known for his ministry among lepers, also expressed deep concern for the enslaved. In one of his prayers, he asked, “May the Lord ease the burdens of the oppressed and grant them freedom.” On the cultural front, the artist Remy Jungerman’s installation Peepina Devil Maroon critiques how Afro-Surinamese spiritual traditions were stigmatized as “pagan” or “evil” within a Christian-colonial framework—reminding us that true liberation is not only legal but also cultural and spiritual.

Dutch Delay and Slow Awakening

While Britain abolished the slave trade as early as 1807, the Netherlands did not formally abolish slavery until 1863—and even then, Suriname imposed a ten-year “transition period,” effectively extending slavery until 1873. It was not until the 1890s that the Dutch Reformed Church officially condemned slavery in its doctrinal positions.

The Dutch abolitionist movement was late in arriving, but remembrance and repentance gradually began to unfold in its aftermath. In 1963, a commemorative medal was issued with an inscription from John 8:36:

“So if the Son sets you free, you will be free indeed.”

This verse became a symbol of the ultimate truth—that Christian faith must point not to spiritual abstraction, but to real and embodied liberation.

09

Part Six: Now

“If you hold to my teaching, you are truly my disciples. Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

— John 8:31–32

But are we truly free?

The final section of the exhibition invites us to step beyond archival records and painted altarpieces—to face the open wounds, tensions, and unanswered questions of the present. Slavery may have been formally abolished, but its legacies live on—in cultural hierarchies, economic structures, and spiritual scars. We are still living in the aftermath of conversion without freedom.

When Faith Meets Traumatized Memory

On Keti Koti in 2022, a commemorative service was held at the W.L.E. Church in Amsterdam Southeast under the theme: “Are we truly being treated equally?” Tensions among Black communities, the residue of white superiority within churches, and the unhealed trauma of Asian indentured laborers—none of this vanished with the abolition of slavery. Instead, it reminds us that the Gospel, if it is to be real, must enter the particularities of human pain.

Surinamese artist Ruben Cabenda explored this theme through video installations, examining the tension between African traditional religion Winti and Christianity. Though baptized as a Christian, Cabenda found himself estranged from the church after studying Winti. His question was piercing: Why can’t Christianity make space for the religious memory of African descendants? And so we are led to ask: If we proclaim a God who loves all peoples, do we also honor the cultural expressions and devotional practices of those once enslaved?

On May 26, 2025, while researching Winti, I believe I may have deciphered the meaning of a nickname given to me 23 years ago. I once had a Black friend from Ethiopia named John, who was studying dentistry at West China Medical University in Chengdu. His Chinese was fluent, and he often came to my bar. One day, he told me he liked me and excitedly gave me a nickname in what he said was an African language: Aubuku (I recorded it phonetically as I heard it). When I asked what it meant, he said it referred to an ancient heroic figure, but never clarified further.

Recently, I came across the Winti spirit Ampuku, a tree guardian. I began to wonder—could John have meant Ampuku, and I misheard it as Aubuku? The difference between “Am” and “Au,” between “bu” and “ku,” could easily have been lost in accent and sound. If my guess is correct, John may have seen me as a tree spirit who protects humanity.

It made me smile.

Repentance, Remembrance, and Participation

As early as 2013, the Dutch Council of Churches organized a memorial service for slavery—an attempt to atone for years of silence. On June 30, 2023, the Protestant Church of Amsterdam held a liturgy of confession and repentance, quoting Psalm 51:

“Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a right spirit within me.”

This was not merely a ritual, but a public declaration of moral accountability: that the church had once been silent, once complicit, and must now testify to the truth.

The visual design of the exhibition echoed this ethic—constructed from reused and discarded materials: pulp, pallets, reclaimed wood. The message was clear: the legacy of history is not only glory, but also wounds, waste, and the voices of the forgotten. These materials became part of the space’s body, just as enslaved persons once had their bodies commodified—bodies now in need of honor and remembrance.

Where Are You in This Story?

Whose side will you choose to stand on?

Can we admit that our faith practices, our accumulated wealth, even our very church buildings, are not untouched by histories of trade, colonialism, and slavery?

Can we still believe that the Church can become a vessel of reconciliation, rather than a symbol of harm?

Now—it is our turn to answer.

This is not the end.

It is the beginning of another calling.

10

Part Seven: The Room of Reflection

“There is nothing new under the sun.”

— Ecclesiastes 1:9

As an outsider—perhaps precisely because I am one—I was able to walk through this exhibition at the Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht with a kind of detachment. I moved from one display board to another as if reading a dense and painful volume of history, peeling back the layers not to assign blame, but to see—perhaps even from a divine vantage point—this long, twisted, and utterly real chapter of human experience.

What I saw was not just a timeline of events and dates.

Not just perpetrators and victims.

What I sensed was an entire civilization wrestling—violently and vulnerably—between sin and grace.

There was resignation.

There was cunning.

There was greed, and also stubborn conviction.

There was prejudice and blind obedience.

There was the violence of domination and the helplessness of submission.

There was cruelty—but also kindness.

There was hypocrisy, yet also sincerity.

There were lies—and there was uncompromising truth.

There were the whispers of devils—and the blood of saints.

As the psalmist once prayed:

“If you, O Lord, kept a record of sins, Lord, who could stand?”

— Psalm 130:3

To look back at the history of slavery honestly is to admit how few of us would remain standing. It is difficult to declare anyone wholly innocent. Even those later called “liberators” often only tried to do less harm from within the system. The ones who truly resisted—openly, sacrificially—were often compelled by a deep-rooted conviction in the justice of God.

“If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness.”

— 1 John 1:9

And yet what pained me most in this exhibition—what felt both tragic and grotesque—was to see how some once used the Curse of Ham from Genesis to justify slavery. To assert that people of color were divinely destined to be slaves—under the name of “God’s will”—was not only a theological distortion; it was a desecration of both faith and humanity.

That happened more than 400 years ago.

But you and I both know: It is still happening today.

Only now, the justifications may come not from Genesis, but from viral video clips, economic graphs, or a selectively quoted Bible verse.

We humans are experts at using anything—especially religion—to excuse ourselves.

I do not stand here as a judge.

I do not place myself on any moral high ground.

For the Lord has already said:

“Vengeance is mine; I will repay.”

— Romans 12:19

So I remain silent.

All I can do is reflect, remind, and remember.

As the Teacher once wrote:

“What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

— Ecclesiastes 1:9

Isn’t it time we admitted: History is not a straight line. We are not necessarily wiser—only more sophisticated in repeating old tragedies with new packaging.

A Dutch friend once teased me, calling me a “MAMIL”: A Middle-Aged Man In Lycra.

He said: “Once a MAMIL, always a MAMIL.”

To which I replied:

Once humanity sins, unless redeemed, it sins again.

And so I keep reflecting.

I keep writing.

And I keep hoping.