To Be Honest: When It Comes to Food, the Chinese Are Fucking Geniuses

Sorry, I used F* Word

There is no exclamation in the English language more emotionally saturated than “fucking.” Period.

Back in the day, I used to teach English to middle school students at an after-school tutoring center. At the time, many of us were learning English through pirated Hollywood films circulating in the streets of China. Those movies were loaded with borderline sex scenes, action violence, and relentless verbal profanity.

One student once asked me, “Is ‘fuck’ a vulgar word?” That question stuck with me for a while.

When I first learned English grammar, I understood:

If something is good, it’s good.

If something is better than another, it’s better.

If it’s better than the other two of three, it’s the best.

But is there a level of good that transcends even best?

Yes. That would be: fucking good.

So in my personal ranking: good < better < best < fucking good.

I’ve tried other substitutes—extremely good, damn good, freaking good, bloody good—but none of them quite hit the emotional note I was going for. So when it comes to food, I have to say: Chinese cuisine isn’t just “the best.” It’s fucking good.

Of course, that’s a bit of a complex statement. But I stand by it.

So if you see the title “Fucking Geniuses,” please understand: there’s not an ounce of crudeness in it. It’s just that, for lack of a better phrase, I was out of words.

Chinese Cuisine: A Byproduct of a Nation’s Resilience

Last time, I said Dutch food was boring. Honestly? That was a bit disingenuous. I’d been hanging around too many media folks and let the clickbait culture get to me. That comment wasn’t fair.

Why do I say that? Because truthfully, I use the Dutch AVG model (Aardappel, Vlees, Groente — potatoes, meat, and vegetables) to check if I’m eating a nutritionally balanced meal every single day. It’s one of the reasons why—even though I’m older than many of my fellow church members—I can still hop on a bike and cruise 100 to 200 kilometers without breaking a sweat. I believe daily food is a gift from God. So I eat well for Him. I care for this body as His vessel.

So yes, from a nutritional perspective, I genuinely admire the Dutch culinary logic: simple, balanced, and efficient. That’s the mark of a civilized food system.

But then, why is Chinese cuisine so elaborate? Why can a single dish require twelve different steps? Why did we develop such a vast arsenal of techniques—stewing, braising, stir-frying, flash-frying, smoking, curing, fermenting, saucing, pickling, sweet-and-sour, umami-blending, and spicy layering?

There’s only one answer: because life was hard, and we had to find a way to make it bearable.

Europe never endured the same scale of famine, poverty, and war cycles our ancestors faced. So they never had to develop survival skills so intricate. But our forebears, living through material scarcity, extreme climates, and frequent dynastic upheaval, turned to their palates and inner strength. They invented an entire culinary system built to transform anything edible into something delicious. Chinese cuisine exists to turn the inedible into delight, to make unbearable days worth living.

That’s why I say: Chinese food isn’t just about flavor. It’s a cultural, historical, and emotional solution system. It reflects a set of virtues: perseverance, diligence, frugality, and respect.

Chinese cooking is the fragrance of wisdom—and tenderness born out of hardship.

The Virtue System of Agrarian Civilization

Since I’ve said earlier that Chinese cuisine is an expression of a “moral system,” let’s follow that logic a little further: what exactly are the virtues of Chinese culture?

To answer that, allow me to call upon none other than Friedrich Nietzsche. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Chapter 15: “Of the Thousand and One Goals,” he delivers a striking proposition: virtues are born of environment. It’s a brutally simple idea—and it works. Try applying it to your own cultural context. You might be surprised at what you discover.

Let’s start with nomadic societies. Picture the open steppe: endless grasslands, not a tree or bush in sight. It’s an environment made for herding. Livestock graze and convert the sun’s photosynthetic work into protein and fat, and the people live off that. The herds walk and eat, and their keepers must move with them—hence, horseback riding. They train dogs not just as tools, but as family. To catch a rabbit, repel wolves, or fend off rival tribes, they need arrows. So they become expert archers.

Now imagine you’re a nomad father. Your daughter’s looking for a husband. What kind of man are you hoping she brings home? The answer isn’t hard: he’d better ride and shoot. A guy who knows how to plow a field? Useless. There’s nothing to farm out here. So, in that cultural context, horsemanship and marksmanship climb straight to the top of the “virtues of manhood” list. As for smoking, drinking, or gambling? Sorry—not very heroic in this part of the world. (I am sorry for this section of contents, someone told me that it sounded like the parents were manipulating the personal life of children. However, the parents do have the right or freedom to hope for something good for their children, in a good way, not interfering. )

Now take that same horse-riding, arrow-slinging superstar and drop him into central China’s agricultural heartland. Suddenly, he’s out of place. Wild animals are scarce. There’s no need for a horse when the market is just a short walk away. Here, a man’s worth is measured not by his aim, but by his hoe. If you can till the land, you’re gold.

Farming is labor-intensive. It runs on muscle, not machinery. And in that context, more people meant more productivity. This is where the infamous “preference for sons” takes root—not from disdain for women, but from an economic logic: men were simply viewed as stronger laborers in the fields. Thankfully, modernity has seen those ideas evolve, but understanding the origin can help us approach these cultural relics with nuance, not judgment.

So what’s the takeaway?

Chinese virtues didn’t fall from the sky. They were shaped by millennia of farming life—practical, complex, and surprisingly tender in their logic. Our food, our values, and our tools were all born from a long-standing conversation with the land, the weather, and the relentless demands of survival.

Chinese culture wasn’t just built—it was grown. So is the Western Civilisation.

So What Does All This Have to Do with Food?

The answer? Everything — absolutely everything. It’s in every detail.

Let’s start with ingredients.

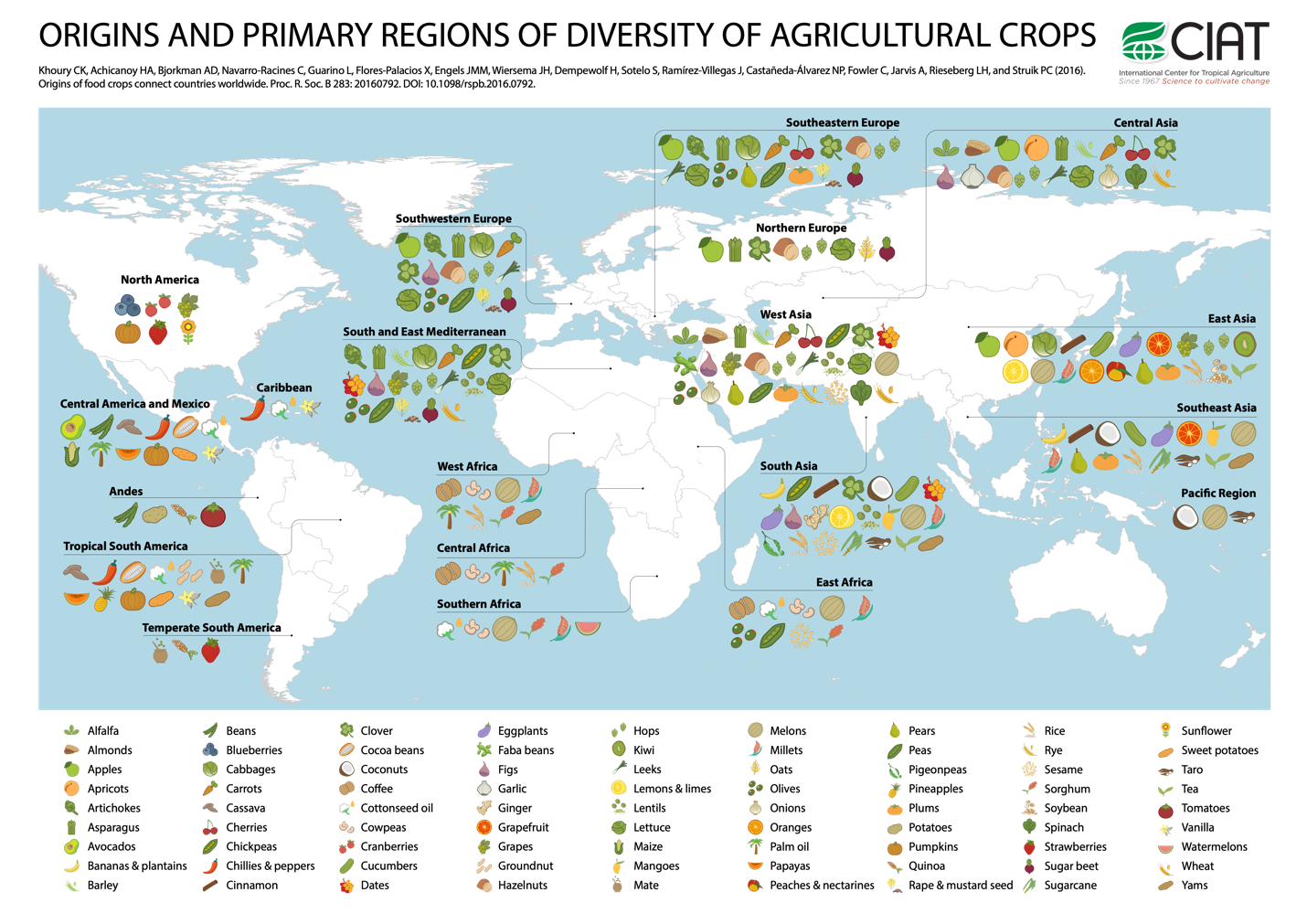

Take vegetables, for example. Agrarian societies are settled by nature, which allows people to plant different crops on the same land through seasonal rotation and intercropping. This kind of intensive, sustainable farming created an astonishing variety of fruits and vegetables. Over time, new technologies like greenhouses, automated irrigation, vertical farming, and hydroponics made the supply even more diverse and dynamic. Compare the produce aisle at your average Dutch supermarket like Albert Heijn with a traditional Chinese wet market — one looks like a pencil sketch, the other like a full-color mural from Dunhuang.

Now let’s talk meat. In traditional Chinese farming culture, people raised animals suited for confinement: pigs, chickens, ducks, geese, and various types of freshwater fish. Cattle and sheep? Not so much. And remember, in the days before electricity and refrigeration, preserving meat was a major challenge. You could slaughter a chicken or pig and eat it the same day, but killing a cow or sheep — which were larger and more valuable — meant you’d have to deal with spoilage. So aside from cooking techniques, preservation became a culinary science: air-drying, curing, brining, fermenting…

Sure, Europe has sausages too — many created for the same reason: to get through the winter. But the Chinese took that impulse to “waste nothing” and turned it into a philosophy. Not just storing food, but inventing entirely new ways to savor it. And this reveals a deeper core value of agrarian China: conserve and revere. Farmers knew that harvests depended on the heavens. Today’s abundance might be gone tomorrow. So you ate with gratitude, finished every bite, and made “nothing wasted” a sacred virtue — not just a habit, but a way to survive.

That’s why food holds a near-spiritual place in Chinese culture. If it can be eaten, it shouldn’t be thrown away. That’s the earliest form of circular economy — long before we had a name for it. As for how to eat well and eat smart? We’ll get to that.

Another factor: China’s sheer size and ecological diversity. From tropics to tundra, mountains to basins, the country is home to nearly every kind of climate. That means nearly every kind of ingredient is within reach.

All of this brings us to one simple, powerful conclusion:

But that kind of abundance brings its own set of problems.

First, complex textures. Then, ever-shifting flavors.

Picture it: animal organs, oddly shaped roots, bold-smelling spices, and fermented oddities. Turning these tricky ingredients into something not just edible — but delightful — takes serious skill. It requires technical mastery and the wildest kind of culinary imagination.

Put differently:

It’s the Chinese people’s reverence for ingredients and relentless creativity that gave birth to this vast, nuanced, and deeply thoughtful philosophy of cooking.

Culinary Technique: Chinese Cuisine as the Art of Micro-Sculpture

Chinese cooking was never meant to be simple. From the very first step—preparing the ingredients—it demands precision, care, and, above all, intentionality.

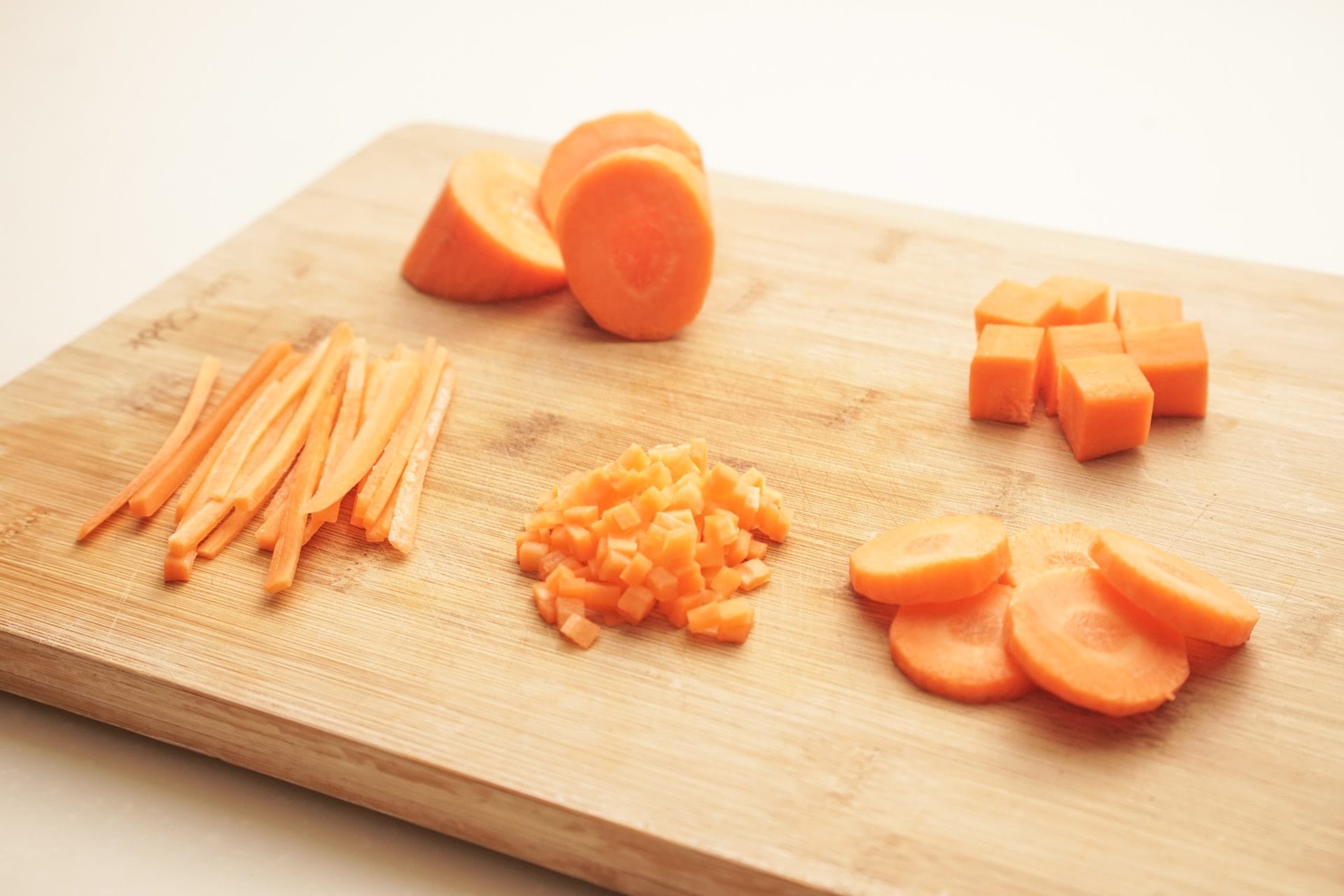

Every ingredient comes with its own question: how should it be cut? Cooked? Seasoned? How can its flavor be drawn out, its texture made tender, its odor refined, and its color enhanced? The answer lies in one of the most underrated arts in the kitchen: knife work. But don’t be fooled—this isn’t just slicing. This is choreography. You’ve got slicing, shredding, dicing, mincing, smashing, scoring, julienning… Every cut has a purpose. Every movement is calculated. Honestly, I’ve never seen this level of complexity in Western kitchens.

And then there’s heat. Fire. Wok. The rhythm and soul of Chinese cooking lives in the harmony between flame and vessel. There are enough cooking methods to fill a poem:

Stir-fry, flash-fry, dry-fry, steam, boil, braise, deep-fry, glaze, simmer, roast, pan-sear, slow-stew…

Each technique has its own rules, timing, and secrets—many passed down like old family scrolls, barely written but deeply memorized.

Let’s talk seasoning. In Sichuan cuisine alone, flavor mastery reaches its absolute peak. Traditional Sichuan cooking recognizes twenty-four core flavor profiles. You might know a few: mala (numbing-spicy), savory-sweet, sweet-sour. But have you met yu-xiang (fish-fragrant), hongyou (red chili oil), suantian (sour-sweet), hula (burnt-spicy), or the elusive strange flavor? Now throw in the global influences of modern gastronomy, and the system only continues to evolve.

To be honest, this part simply couldn’t be condensed any further—after all, what I’ve shared so far is just the table of contents and introduction from the Sichuan culinary handbook my master passed down to me. To truly explain this art, you’d need an entire book, and probably a lifetime to practice and understand it. But my master once told me something that’s stayed with me ever since:

“True transmission takes just a single sheet; false teaching fills ten thousand scrolls.”(真傳一張紙,假傳萬卷書。)

Now that I live alone in Europe, there are times when I want to recreate a dish from home, but I can’t find the right spices. So I go to the Asian market, pick out a few close substitutes, and blend them myself. The reason I’m able to pull it off isn’t because of any special talent, but because of what I learned from my Baijiu master, Chen Qingming, and my uncle-in-craft, Chen Jingyu. They taught me how flavors intertwine and how to layer aromas and tastes in the right sequence. With that understanding, I can bring those familiar flavors back to life—even when ingredients are scarce.

At this point, someone might ask, “Isn’t sweet and sour the same as lychee flavor? Aren’t they both sweet and tangy?” That’s exactly what I asked my master when I was training in Sichuan cuisine. He gave me a simple reply:

“Taste carefully—sweet and sour hits sweet first, then sour. Lychee hits sour first, then sweet.”

I took a bite, and wow—he was absolutely right.

The Invisible Contribution of Chinese Cuisine to the World

Before I came to Europe, many Chinese friends had a burning question: “The Netherlands raises nearly a hundred million chickens—so where on earth do all the chicken feet go?”

Turns out, they come to us.

In many parts of Europe, chicken feet are considered waste. Not even food. But thanks to the Chinese love for gnawing on bones and collagen, these so-called leftovers found a second life—and a market. And through that market, the economic value of the whole chicken goes up. Just imagine: if Chinese buyers weren’t around to scoop up these unwanted parts, wouldn’t chicken breasts—your so-called ‘prime cuts’—be a little more expensive?

So maybe next time, before you dig into your affordable grilled filet and say grace, you might want to add a line: “And thank You, Lord, for the Chinese people who eat the parts we don’t—so we can keep eating the parts we like, for cheaper.”

And this isn’t an isolated story.

Let’s talk pork intestines. Europe produces them, yes—but it’s often the Chinese who put them to use. Shipments of pig intestines regularly roll east on the China-Europe Railway Express. Some are used to extract heparin, a blood-thinner essential for treating strokes and blood clots. Others? Turned into sausage casings. Yes, that bratwurst you’re eating may owe a quiet debt to Chinese hands. These processes happen in Chinese factories, which then export raw pharmaceutical materials to the likes of Pfizer and Novartis. So if someone in your family is taking medication for blood clots, maybe offer a silent thanks to the “people who eat everything.”

This, by the way, isn’t just my opinion—it’s biblical. “All things work together for good” (Romans 8:28). Even if you don’t understand how economies, cultures, or sausage skins connect, it doesn’t mean the interdependence isn’t real. I hope people learn to value each other more. And if not, well, maybe they need to read a bit more about how the world actually works.

To put it another way: Chinese cuisine may not be the most beloved cuisine in the world, but it turns waste into wonder. It gives value to the discarded. And in doing so, it feeds the world’s agricultural economy in quiet, practical ways.

Back when I lived in Amstelveen, my favorite Friday ritual was visiting the outdoor market at Stadshart. One day, I spotted pig trotters at a local slagerij—dirt cheap. I was thrilled. But a friend told me: “You know, they used to give those away for free.” But as more Chinese shoppers started showing up, prices went up. That’s how the market works. A pig’s foot, once headed for the bin, now teaches us Economics 101.

So let’s be honest: Chinese cuisine is not born from indulgence. It was born from hunger, from hardship, from the desperate need to make something out of nothing. It is a food philosophy forged in scarcity, not in surplus. That’s why Chinese people have such extraordinary culinary creativity—we had no other choice.

If you think of yourself as a bold foodie, don’t just hunt for exotic sauces in the supermarket. The real adventure might be waiting down a narrow alley in some dusty Chinese town. And don’t be surprised if it sparks a revolution—in your taste buds, and maybe even your worldview.

Do Chinese People Really Eat Everything?

Let’s settle this right away: No, we don’t.

But let’s also be fair—Chinese people are a lot more adventurous than most Europeans when it comes to food. Take crayfish, for instance. These red little buggers caused chaos in the U.S., invaded local ecosystems, and became a headache for everyone involved. But when they reached China—ironically, as an invasive species—they didn’t just survive. They became dinner. And not just dinner. They became a thriving industry, farmed en masse, cooked to perfection, and nearly eaten into endangered status.

Or look at Australia and its infamous rabbit problem. There’s a saying in China that goes: “No rabbit walks out of Sichuan alive.” It’s dark. It’s funny. And it’s kind of true. There’s a city in Sichuan called Zigong, famous for its ancient salt wells, fossil-rich soil, and natural gas fields. But ask any local and they’ll tell you: Zigong is better known for its spicy, tongue-numbing mastery in cooking rabbits and fish. That place is so serious about seasoning, even the rabbits come with built-in anxiety.

And there’s more. Tilapia. Duck heads. Pig ears. You name it—we probably turned it into a hot dish somewhere.

Now, on the topic of eating dogs. Let’s be real: it happens. But let’s also be accurate: it’s not the norm. From what I know, only certain regions—like parts of Guizhou or Yulin in Guangxi—have seasonal traditions that involve dog meat. There’s even an old historical account that claims a royal martial monk brotherhood was granted permission by the emperor to eat dog meat. Whether that’s myth or fact is up to the historians. But here’s what I do know: neither I nor anyone around me eats dog. In fact, I own a dog. And he’s the most loyal being in my life.

China is huge—1.4 billion people over 9.6 million square kilometers. If one person in one corner of China eats something strange, calling it “what all Chinese people eat” is like spotting a guy in Italy eating pineapple pizza and assuming it’s part of Vatican doctrine.

Honestly, when Dutch friends joke, “Chinese people eat everything,” I just smile. Because comments like that say more about their limited perspective than about my culture. And if aliens ever visited Earth and looked at us the way some people look at China, they’d probably shake their heads and say, “Earthlings eat poop.”

So next time you hear “Chinese people eat everything,” take a pause. Maybe what you’re really hearing is someone who hasn’t read enough books.

There should be a conclusion

As my elementary school teacher would insist, let’s wrap things up the way we started: When it comes to food, the Chinese really are fucking geniuses.

But behind that genius lies generations of hardship, wisdom, and resilience. And you won’t truly understand it until you step into the depth of Chinese culture. The more you learn, the more layered your emotions may become—you might start with respect, move into fascination, and possibly fall in love.

Speaking of love, let me share a bit from my own journey. Ever since I formally became a disciple of Master Wang Zhilong—one of the great names in Sichuan cuisine—I’ve hosted authentic Chinese dining experiences across several Dutch cities. Of course, no proper Chinese meal goes without a glass (or three) of Baijiu.

These events are always lively. I remember one time, a Dutch friend walked up to me, plate in hand, tears in his eyes, smile on his face, nose still tingling from the spices, and said: “Can I please have one more bowl of that spicy beef… whatever it is called… It’s incredible!” That was his first encounter with Shuizhu Niurou (Sichuan-style boiled beef). And probably the first time he learned that yes—you can cry from spice and still beg for seconds.

Another moment I’ll never forget: a Christian sister here in the Netherlands looked me dead in the eye and said, “I’ve never in my life eaten pork with any fat on it. But your Hui Guo Rou—I had several pieces!” The astonishment and joy on her face were more convincing than any Sunday sermon I’ve ever heard.

That’s the magic of Chinese food. It doesn’t just tease your taste buds—it invites your soul into the story.

So let me warn you now, my friend: Be cautious with your first bite—because you may never want to stop.

以上

Hans Ngo Wurfbain

Utrecht, the Netherlands

1st, May 2025