(Warning: Super Long)An Earthquake Killed 69k People In 2008 Near Chengdu

The Anniversary Returns

It is that time of the year again.

Today is Monday, and like every Monday evening, we gather at XRDS International Church for MNP—Monday Night Prayer. It’s a quiet moment in the week when we lay down the weight of the world—its sorrows and its hopes—before God.

But tonight, my heart is especially burdened for a group of people who were once in the spotlight of the entire world, but who have gradually faded from its memory.

On May 12, 2008, a magnitude 8.0 earthquake struck Wenchuan County, Sichuan Province, China. In a matter of seconds, the earth cracked open, mountains slid, buildings collapsed, and entire families were torn apart.

According to official statistics, over 69,000 people lost their lives, 68,636 of them in Sichuan alone. More than 374,000 were injured, and 18,222 remain unaccounted for—even today.

These are not just numbers.

Each figure marks a severed bond—a mother who never came home, a child whose laughter vanished, a friend whose name was never called again. They are not rows in a spreadsheet, but stories halted mid-sentence, dinners left uneaten, doors that will never open again.

Seventeen years have passed. The world has moved on. News cycles have closed. But for the survivors, the tremors never truly stopped. Many still live with the silence of those they lost, and with wounds that have turned inward, becoming part of their everyday lives. They are not in the headlines, but they walk among us—still rebuilding, still remembering.

Tonight, I ask you to pray with me—for them.

For those whose bodies have healed, but whose souls are still recovering;

For those who walked out of the rubble but have yet to find direction in life;

For those whose destinies were reshaped by the quake—

Who may now be construction workers, doctors, teachers, or simply a father, a mother, a neighbor.

May the Lord heal their hidden wounds.

May He wipe away their tears and replace ashes with hope.

May they no longer be defined as survivors, but as rebuilders, witnesses—people who live by grace.

In a world still shaking with uncertainty, may we not forget one another’s suffering.

And may we never lose the courage to intercede for one another.

Because the prayers of love—are the arms of the cross extended into the world.

Amen.

_SSL27231.JPG/1200px-2008%EB%85%84_%EC%A4%91%EC%95%99119%EA%B5%AC%EC%A1%B0%EB%8B%A8_%EC%A4%91%EA%B5%AD_%EC%93%B0%EC%B4%A8%EC%84%B1_%EB%8C%80%EC%A7%80%EC%A7%84_%EA%B5%AD%EC%A0%9C_%EC%B6%9C%EB%8F%99(%E5%9B%9B%E5%B7%9D%E7%9C%81_%E5%A4%A7%E5%9C%B0%E9%9C%87%2C_%EC%82%AC%EC%B2%9C%EC%84%B1_%EB%8C%80%EC%A7%80%EC%A7%84)_SSL27231.JPG)

A Life Rebuilt

It wasn’t a sudden breakdown.

It was more like a silent, methodical unraveling—one that pulled me apart bit by bit, quietly, until I was forced to rebuild myself from the ground up.

I used to believe that life was just a steady march forward—like cycling: keep pedaling, and eventually you’ll arrive. But during that season, I came to realize that sometimes, “just keep moving” is another way of running away.

I found myself caught in a battle that looked calm on the outside but was full of undercurrents within.

What I was fighting wasn’t the world—it was me. More specifically, it was a long-ignored, slow-burning form of PTSD.

It wasn’t dramatic, like what you see in movies. It didn’t involve nightly nightmares or screaming in the dark.

It was quieter than that—like a slow boil. The kind that drains you from the inside out.

I never realized how far it had gone—not until I found myself standing on the edge of a 21st-floor window.

It wasn’t a dramatic “I want to jump” moment. It was more like a dissociated haze of “What am I even doing here?”

I had opened the window just to get some fresh air, and for some reason, I stood there frozen, staring at the ground for a long time.

Then, strangely, my brain began to compute.

I started recalling high school physics—the free-fall formula:

½·g·t² = h

Gravitational acceleration is 9.8. This floor is about 63 meters high. So the fall would take around 3.6 seconds.

Then I wondered: if I wore a thick coat, would it increase air resistance and prolong the fall just slightly? If I leaned forward, would the impact point shift two meters away from the building?

These thoughts weren’t a violent impulse.

They were cold, methodical calculations—like I was prepping an experiment.

And then I looked down. That’s when it hit me.

A chill spread from my chest to my fingertips, and my hand instinctively clutched the window frame. I realized something was very wrong.

I’m mildly afraid of heights. Under normal circumstances, I would never have stood like that.

I didn’t cry. I didn’t scream. I just quietly closed the window, sat back down on my bed, and stared at the ceiling—motionless.

The next day, a friend handed me a few small pills—antidepressants from Pfizer.

He looked at me seriously and said, “Try one. It might help.”

So I did.

And everything slowed down—my heartbeat, my thoughts, my soul.

It was like someone had plucked a string deep inside me and turned me to mute.

I wasn’t anxious anymore. But I couldn’t think. I couldn’t feel. I couldn’t laugh. I couldn’t cry.

That wasn’t me.

So I never took a second pill. The box sat on my shelf, unopened, until it expired and I threw it away.

Sometimes, I think I owe my friend an explanation.

But really, the explanation I owe is this:

I would rather hurt and stay human than live numb and feel nothing.

People often say I’m “strange.” Maybe I am.

But then again, how many well-dressed, polite people walking among us are carrying shrapnel in their souls?

When you’ve stared death in the eye, you stop worrying about many things.

And you stop caring what people think.

To this day, I don’t believe I’m still alive because I’m strong.

I believe I’m here because my mission isn’t finished.

Because there are still roles I need to play, stories I need to tell, prayers I need to offer.

I’m not ready to “retire” yet—not to meet Jesus, and not to join the grandparents who are waiting for me somewhere beyond this world:

Grandpa, grandma, yéyé, nǎinai… I know they’re smiling, waving from some window in eternity.

But it’s not time for me to go home.

Today is the day I choose to speak.

Not to gain pity.

But to pray—for all who are still struggling.

You are not alone.

I’ve lived through your nights.

I’ve stood on your windowsill.

I cannot take away your pain,

but I understand it.

And now, I want to show you a few photos.

Photos that used to make me cry in the middle of the night.

But today, I will lend them my voice, and tell a story—

a story of falling, fighting, believing, healing… and riding on.

The Earthquake Hit

It happened at exactly 2:28 p.m. on May 12, 2008.

That afternoon, my colleague—and brother in faith—Ouyang and I had just finished lunch at a little diner tucked beside Yandaojie Middle School. We were strolling slowly back to the office, located on the third floor of the Sichuan Provincial Tourism Bureau at 65 Renmin South Road, downtown Chengdu.

We had barely sat down when the building began to gently sway.

At first, it was subtle—the kind of motion you might chalk up to someone moving heavy furniture in the next room. But then the ceiling lights began to swing wildly, carving arcs in the air like a pendulum on a playground.

I froze for a second, squinting upward.

My brain struggled to compute what was happening.

To be honest, it was my first earthquake, and I had no idea how to react. It took me nearly twenty seconds to realize:

“Wait… this isn’t structural settling.

This isn’t someone dragging desks around.

This… is an earthquake.”

While I was still frowning and trying to rationalize the movement, Brother Ouyang had already shouted ‘Earthquake!’ and bolted out of the office—faster than he’d finished his noodles that morning.

Me? I didn’t follow immediately.

Instead, in what now feels like an absurd moment of misplaced calm, I tidied my desk. I checked my phone and wallet. I even made sure everything was zipped up neatly in my bag.

In hindsight, my departure could be described as… graceful evacuation.

Just as I turned to leave, I noticed Ouyang’s keys still on the desk—he must’ve forgotten them in the rush. I let out a quiet “Oh no,” scooped them up, grabbed my bag, and finally ran for the stairs.

From the moment the quake began to the second I reached the ground floor, the whole thing probably took less than a minute. Not bad for someone without a single drill under his belt—I guess you could call it a street-smart version of earthquake protocol.

Out in the parking lot, I looked across the street at the towering Minshan Hotel, still swaying like it had a bit too much to drink. Then, crash—a couple of windowpanes from the upper floors came shattering down, exploding on the pavement with a deafening bang. People nearby screamed and scrambled in panic.

And just as I was still trying to process the glass crashing onto concrete, a surreal scene unfolded:

a group of hotel guests in bath towels—some barefoot, some dripping wet—came sprinting out of the Minshan lobby, their faces pale with shock.

For a split second, my mind stalled on one thought:

“Wait, people were showering at this hour?”

It felt so absurd that I almost wondered if I’d stumbled into the behind-the-scenes of a disaster movie.

When I finally turned my attention back to the Tourism Bureau building behind me, I realized the front plaza was now packed with people—faces I’d never seen before, though we all worked in the same building.

Everyone had just come pouring out of their offices.

Everyone looked just as stunned as I felt.

Then I noticed something else—up on the roof, the giant “Sichuan Tourism” billboard was swaying violently, bobbing and twisting like one of those inflatable air dancers in front of a gym.

It was flailing its limbs in the wind like it had a mind of its own, almost… seductively. Hypnotically. Ridiculously.

And I thought:

“If that thing falls down, what a tragic joke it would be—‘Tourism’… now it’s forced tourism.”

That was the moment it hit me:

An earthquake isn’t a novelty. It’s not an exciting story. It’s a weight. It’s a rupture. It’s a line drawn in a life.

It changes fates in seconds.

And I—just one person among tens of thousands—was lucky enough to run fast, stay upright, and somehow remember to grab my colleague’s keys.

When in Doubt, Don’t Lie. First, Go Home to Mama.

The very first thought that flashed through my mind was:

I have to get home to my mom. Now.

I pulled out my phone to call her—but nothing went through.

The signal was gone. Completely paralyzed.

Everyone in the city must’ve been dialing at the same time. It was as if tens of millions of dragons had tried to squeeze through the pipes of China Mobile and China Unicom, clogging the whole thing beyond recognition.

There was no time to think. I jumped onto my electric scooter and sped off like a bullet. It was pure instinct—I rode faster than I ever had, even faster than on days I was late to work.

I tore through the streets of Tianfu Square, Taisheng Road, Ma’an Road—places I had passed a thousand times. But that day, it felt like I was riding through another planet.

People filled the roads—not running in panic exactly, but spilling into the streets like the entire city had decided to step outside for some fresh air.

Taisheng Road, usually one of the busiest, most crowded places in Chengdu, was now chaos.

Tiles rained down from old rooftops like someone had flipped over a giant Mahjong table.

Shards clattered and exploded across the pavement with deafening force.

Some were crouching under trees, sobbing with their heads in their hands.

Some had fallen to the ground.

Others ran through the street waving their phones toward the sky, shouting:

“Hellooooo? Can you hear me or not?!”

Most just stood in the middle of the road—frozen, blank-faced—like the whole world had suddenly gone out of focus.

I didn’t stop once. I raced all the way to our apartment complex and slammed the brakes at the gate. I ran inside, heart pounding.

And there she was.

My mom… was still playing Mahjong.

She and her friends were in the ground-floor courtyard, cards neatly laid out, unbothered.

They’d felt the tremor, sure—but it hadn’t been that strong down there. Nothing like what it felt like on the upper floors.

They hadn’t even realized it was an earthquake.

At one point, they’d actually gotten into a small argument, thinking someone was shaking the table.

“Why are you shaking your leg again?”

“I didn’t! Your table’s uneven!”

“I’m talking to YOU—my three-dot tile flew across the board!”

Only after someone glanced at the ground did it click:

It wasn’t the leg-shaking. It was an earthquake.

But after a few startled comments and some mild debate, they just shrugged and reshuffled the tiles.

Game on.

So when I burst through the door, breathless and pale,

my mom didn’t even look up.

She calmly drew a tile, glanced at it, and said in the most casual voice:

“Why’d you come home? Nothing happening at work?”

I nearly collapsed on the spot.

This is Chengdu.

Even if the earth shakes and the sky falls—Mahjong goes on.

And these aunties, these tough-as-nails old ladies,

they have nerves stronger than the city’s concrete and rebar.

They weren’t panicking.

Which, strangely enough, made me feel a little better too.

Taking Action

After making sure my mom was safe in our apartment courtyard, I didn’t say much. I simply turned and went straight to the basement.

Down there, tucked in a dusty corner, was an old “high-end” shortwave radio—the kind we used to call “enemy station eavesdroppers”. I had brought it with me years ago from Beijing, back when I was still a student, trying to improve my English by listening to the BBC.

I never imagined that one day, this relic would become my lifeline.

I remembered clearly: in every disaster movie I’d ever seen, when all communication breaks down, there’s always one thing still speaking—the radio.

So I turned it on.

There was something almost ceremonial about the action.

I reached out and twisted the slightly stiff tuning knob.

“Kzzzt—shhhh—pop—sssssh—”

The static crashed through the speaker in waves, like white noise trying to drown out the world.

Then suddenly, a voice broke through.

Chengdu Traffic Radio.

The host was speaking quickly, with a strain in his voice:

“We’ve lost contact with Beichuan. The city… may have been destroyed by the earthquake.”

I froze.

Then, another voice took over—this time quieter, trembling.

“The total population of Beichuan County and its surrounding area is… over 200,000.”

And then—silence.

I stared at the radio. My thoughts hit a wall.

“We’ve lost contact.”

Was that temporary?

Or did it mean—“this city is gone”?

Two hundred thousand people?

What does that even mean?

Are they… all gone?

I didn’t want to finish the thought.

But I knew one thing: I couldn’t sit still. I had to do something.

Phones were still dead—calls wouldn’t go through.

But then I discovered something that sparked a flicker of hope:

The China Telecom ADSL internet was still working.

That was enough.

I booted up my computer, logged into every platform I could access—QQ groups, MSN, forums.

I started sending out messages everywhere:

To my travel industry contacts,

My cycling groups,

The trail running forums I’d once joined.

If the government couldn’t reach Beichuan,

maybe we could reach each other.

Urgent Call to Action

I wrote:

⚠️ Dear friends, I have two urgent action proposals:

Tonight, let’s gather at the Red Cross blood donation station at Hongxing Road Square for a group donation. Blood is the most immediate form of help we can offer right now. Bring your ID—let’s go together.

Tomorrow morning, May 13th, I plan to head toward Beichuan to support frontline relief efforts. I ask for your help in gathering supplies: tents, sleeping bags, emergency food, disinfectants, headlamps, hiking backpacks—bring whatever you can.

We may not be able to enter the disaster zone right away, but we must be ready.

This is not about appearances. It’s about presence. About showing up.

This wasn’t the moment to ask whether I could change the world.

It was the moment to ask:

Do I even have the right to do nothing?

This wasn’t a carefully planned humanitarian project.

It was a gut-level response. A reflex of conscience.

The crackling voice on the radio had hit me like a hammer to the chest.

It woke something deep inside me—something that still believed in mutual aid,

still believed that if we stood together, we could do something.

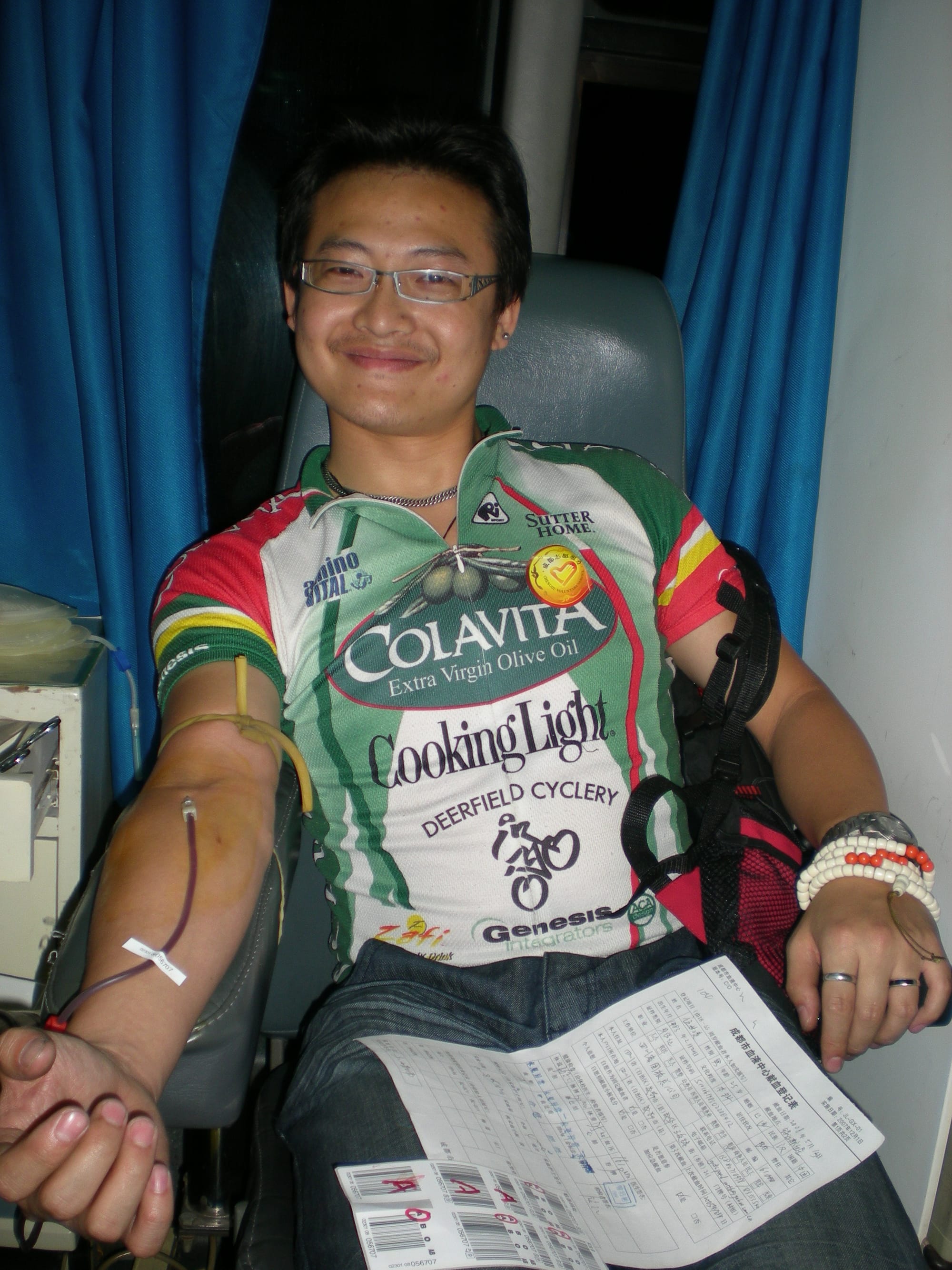

Hongxing Road: The Night of Blood Donation

By 11:00 p.m., I had gathered around 27 people who had committed to traveling with me to Beichuan. In the meantime, nearly a hundred others had joined us in our first mission: to donate blood.

When I arrived at Hongxing Road Square around 11:40 p.m., the line outside the Red Cross blood station was already stretching over a hundred meters long. By rough count, there were more than 300 people waiting to give blood.

It was the first time in my life I had ever witnessed something like this.

To be honest, I was overwhelmed—not with fear, but with something fierce and human and urgent.

People stood in line, not in silence, but in shared memory.

Everyone was recounting their own version of the earthquake just hours earlier.

One man had been sitting on a toilet on the upper floors of an office building—when the shaking hit, water and waste splashed up and hit him.

Another had been watching TV at home when the screen toppled forward, and the refrigerator crashed to the ground. He said he couldn’t even grab food if he wanted to.

One girl had jumped from a second-story window—parkour-style—and somehow landed without a scratch.

Someone else had been napping and, upon waking mid-quake, thought they had suddenly developed a neurological disorder.

Everyone had a story.

Everyone remembered chaos.

We waited nearly four hours.

It wasn’t until around 2:30 a.m. that it was finally our turn to go through the pre-donation screening—filling out forms, blood typing, weighing in. The kind of procedures that feel both medical and bureaucratic at once.

Back then, I still had a baby face. There’s a saying in Chinese that always makes me smile:

“Time is a pig-killing knife.”

These days, I find myself working hard to improve my “aura” just to offset the wear-and-tear time has inflicted on my face.

In this photo, you can see me standing among nearly a hundred fellow outdoor sports enthusiasts, lining up to give blood. I remember someone joking:

“Even if we don’t make it back from the disaster zone, at least our blood will.”

Of course, scientifically speaking, that makes no sense—our donated blood would’ve been metabolized by the body within a few days.

But we were young then. What mattered was the feeling—that we were doing something that counted.

Looking back now, I realize there was one thing I didn’t do well—I didn’t spend enough time with my girlfriend before leaving.

In fact, I didn’t even say a proper goodbye.

No heartfelt conversation.

No lingering hug.

Not even a kiss.

At the time, I thought I was being brave. Focused. Righteous.

But now I understand her emotions better. She wasn’t trying to stop me.

She just… didn’t want to lose me.

Preparations Before Departure

May 13, 2008 – A Street-Side Assembly in Chengdu

It was the morning after the quake—10:00 a.m. on May 13.

The street in front of our old residential courtyard suddenly came alive.

One vehicle after another pulled into the narrow lane, loaded not only with supplies, but with people’s determination.

There was a luggage van from a travel agency we knew—it normally took tourists to the airport.

There was a freight truck from a sneaker shop—its back seats had been ripped out to make room.

There were service vehicles dispatched by a cycling buddy’s construction company.

This wasn’t a coordinated effort.

There were no ranks, no uniforms, no official orders.

But at that moment, the street itself became a magnetic field, drawing in volunteers—old friends, new faces, cycling teammates I’d only nodded to at water stations during trail races… they all came.

We held a quick but solemn mobilization meeting at the entrance to the alley, then circled up on the roadside for what we jokingly called a “human-shaped strategy meeting.”

I gave three key reminders:

- We are not heroes—we are the living. We go in safely, and we come back safely.

I said,

“We’re not going there to be the stars of the show. This is not a stunt. We do what we can, and our safety comes first. Otherwise, we become the ones others have to rescue.”

Everyone nodded.

Someone who had planned to bring paragliding gear decided to leave it behind.

He laughed and said,

“Yeah… probably too flashy for this.”

- Departure set for 1:00 p.m.

Until then, we split up—go door-to-door asking for donations.**

We locked in our departure time: 1:00 p.m. sharp.

Before that, each of us went to nearby residential blocks, knocking on doors and encouraging people to donate warm supplies—old clothes, sheets, blankets, anything that could help someone stay warm.

One elderly woman dragged out an old army-green quilt and muttered softly,

“My husband used this when he was in the military. Take it to Beichuan.”

Someone else handed over a brand-new baby blanket she’d just bought for her grandson.

“It’s fine,” she said. “He has others.

They probably don’t even have the ground to sleep on.”

- Bring food. Don’t collapse on the road.

I reminded everyone:

“Pack your own food. Even if it’s just a few energy bars or a couple chocolate bars—bring something.”

The supermarkets around us had already been stripped bare.

Not even bottled water remained on the shelves.

This was the critical 48-hour window after the quake. Everyone was preparing however they could.

One rider showed up carrying two huge boxes of instant noodles.

Someone else had a backpack filled with rice from their kitchen.

Another brought a metal lunchbox packed with sweet potatoes and sticky rice his mother had steamed that morning.

This wasn’t a professional rescue operation.

This was a group of ordinary people responding in an extraordinary time.

There were no tactical formations, just earnest faces, some of them slightly nervous.

There were no unified slogans, just gentle reminders:

“Did you bring enough water?”

“Are you physically up for this?”

“Don’t overdo it.”

The skies over Chengdu that day were gray and heavy.

But our hearts burned bright.

This was a departure born on the street—with no title, no headquarters,

only the trust between us, and a shared conviction that we had to go.

When Disaster Struck, Our Courtyard Moved First

Not long after, we completed gathering supplies. Blankets, water, dry food, medical kits… were packed into every available space. Each vehicle turned into a makeshift “mobile warehouse of hope,” stuffed to the brim from trunk to roof.

Our old courtyard happened to be in a uniquely strategic location. Just 15 hundred meters from Chengdu’s largest home appliance market, Chenghuangmiao, and not far from one of the biggest wholesale trading hubs, Hehuachi, in all of China. Because of this, many courtyard residents made a living through small businesses—some in electronics, others in wholesale. They looked simple and unassuming, spoke in thick local dialects, dressed casually—you’d never guess they had anything to do with “business success.”

While we were loading the trucks, a man wearing glasses stood at the roadside, watching. He lived in one of the inner units of our compound. We barely had any contact before. That day, he stood silently at the edge of the crowd, eyes filled with curiosity.

“What are you guys… up to?” he asked.

Without even pausing from my packing, I replied, “We’re heading to Beichuan. To help.”

He nodded. Didn’t say more. Then turned and walked away.

About ten minutes later, he came back—with a thick wallet in hand. He walked straight up to me and said:

“Brother, I can’t go with you. Got some family matters I really can’t leave behind. But… here—this is something from me. Just to do my part.”

He took out 2,000 yuan in cash and handed it to me.

“Use it on the road. Get yourselves something to eat and drink. And be careful. Please.”

I was sweaty and exhausted, busy coordinating everything, hands dirty from the work. I quickly thanked him, took the money, and went back to organizing. Honestly—I didn’t even count the bills.

Just a few minutes later, he came back again—with another 1,000 yuan in hand.

“I thought about it,” he said. “There’s quite a few of you. Maybe 2,000 isn’t enough. Here’s a little more.”

I froze. Before I could say much, he just smiled, patted me on the shoulder, and turned to leave.

In that moment, my heart tightened. I felt my eyes sting.

This—this is the kind of Chinese people I know.

They may seem scattered in daily life—minding their own business, indifferent to each other, no grand coordination, no heroic slogans. Sometimes you’d think everyone’s just a stranger to one another. But the moment something truly serious happens, the entire street, the whole neighborhood, the city—moves. Like a powerful tide beneath the surface, swift and unified.

No fanfare. No grand mobilization.

But everyone is doing something.

This… is what “when one is in trouble, all lend a hand” really looks like—raw, grassroots, and unfiltered.

Chengdu people are famously laid-back. Mahjong, teahouses, cafés, slow living. It’s often impossible to tell who’s who—a person who looks like a retiree taking out the trash could be a wholesale tycoon. A business negotiation?

It doesn’t happen in boardrooms.

It happens around a hotpot table. After a few rounds of heavy baijiu. When people are half-drunk and helping each other walk back to the office, dizzy and flushed, where they sign the contract with trembling hands.

It’s not a joke. It’s what I’ve lived.

Sometimes, I share these stories with Dutch friends. They struggle to understand:

“Why would anyone get drunk to do business?”

But those Dutch friends who’ve spent time in China—they just smile knowingly when I bring it up.

We lock eyes.

Nothing more needs to be said.

That Moment in Chengdu

Though the epicenter was in Wenchuan, Chengdu too felt the quake—deep and clear.

Technically, downtown Chengdu lies over 70 kilometers away in a straight line. But more crucial than distance was the city’s geological structure. Soft soil layers—usually considered a weakness—turned out to be a saving grace. Chengdu was like a giant shock absorber, taking the blow with surprising grace.

When the quake hit, what we experienced was roughly equivalent to a magnitude 5 tremor. There were aftershocks in the days that followed, each slightly gentler than the last. But miraculously, no large-scale building collapses occurred in the city.

Instead, we saw the earth ripple subtly—up, down, side to side. The entire city felt like it had transformed into a massive waterbed swaying in the wind. You could feel danger approaching… but it never quite pounced.

Once television and radio resumed, the very first public announcement rang out loud and clear:

“Do not stay indoors. Head to open spaces.”

That single line became an unspoken citywide pact.

Within hours, parks near my home were flooded with people. You could barely find room to stand. Where once people walked dogs, danced in the square, or strolled under trees, now there were blankets, mats, foam pads—Chengdu residents had simply moved into the parks.

Even the roads took on a new identity—turned into makeshift badminton courts, soccer fields, playgrounds. Some pitched tents between parking spots, others brewed tea by the median strips. The air was thick with panic, resignation, awkward humor, and a strange kind of streetwise playfulness. That uniquely Chengdu spirit—half anxious, half amused—was alive and well.

Schools were closed. Office towers were shut. Deliveries stopped. Construction halted. Even interior renovations came to a screeching halt. The entire city felt as if someone had slammed a giant pause button. Everyday noise gave way to the collective exhale of a city trying to calm its heartbeat.

And in that moment… the happiest creatures in Chengdu were the mosquitoes.

With millions of humans now sleeping outdoors, the mosquitoes had just been gifted the buffet of a lifetime. No walls, no screens, no sprays. They floated between arms, legs, necks like royalty in a silk-draped banquet hall. Someone quipped:

“We left our concrete homes for safety—and turned the city into a five-star buffet for mosquitoes.”

Toward Beichuan: A Cyclist’s Journey Against the Flow

To reach Beichuan, we had to pass through Mianyang.

Our convoy moved smoothly—likely thanks to the handwritten signs on our vehicles that read “Disaster Relief Transport.” People made way for us, as if instinctively sensing the urgency behind our wheels.

But the closer we got to the epicenter, the heavier the air became—thick and oppressive, like a wet wool blanket soaked through with grief. It pressed down on us, breath by breath.

The ground trembled quietly under our tires as aftershocks passed through. We were moving against the current. Along the way, we had to swerve around mangled vehicles crushed by falling boulders—roofs caved in, windows shattered, like war wreckage pulled straight from a movie set.

Villagers clung to open-back freight trucks, some crammed into the cargo beds, others hanging off the sides—fleeing any way they could.

But the image that silenced me most was this:

A family, trying to carry the body of a loved one out of the mountains.

At first, they tried to take the corpse with them. But the road was long, and the tremors kept shaking down more rocks. The group had to move fast. They couldn’t carry the body anymore.

So they laid it down gently by the roadside.

They wrapped it tightly in a blue industrial tarp—the kind used at construction sites. They knelt, bowed a few times in silence, then turned away and left.

I will never forget that moment.

The act of turning wasn’t a farewell.

It was a tearing.

Beyond that point, the road stopped being a road.

A newly built bridge had snapped in two.

The mountain path had vanished beneath landslides.

We had no choice but to stop the vehicles, unload supplies, and move forward using bikes and shoulder bags.

At a place called Shigu, the terrain was no longer continuous ground but a series of fractured steps and jagged ledges.

One second, we were hoisting bikes onto platforms nearly a meter high.

The next, we were jumping down eroded slopes that threatened to collapse under our feet.

It felt like we had become the Prince of Persia—moving through a crumbling, surreal world, leap by leap.

Then, near the entrance to Beichuan’s urban zone, we were stopped by a unit of soldiers.

A commanding officer stood in our way and spoke firmly:

“Please don’t go any further. Beichuan is now under military rescue control.

Heavy machinery is working inside, and the situation is highly complex.

Many victims are still buried under stone.

You won’t be able to help. You may only add to the danger.”

“All able-bodied volunteers have been redirected to Mianyang Stadium and the old school in Anchang Town.”

We were silent.

But he was right.

We were driven by passion, but few of us were trained in professional rescue. We were here to transport, to support, to organize—not to charge into deadly terrain.

For everyone’s safety, I made the call: we would turn back.

I must admit—I was scared.

The road was narrow, wedged between cliffs and falling slopes. Our drivers dodged rocks and cracks, weaving like dancers between danger and disaster. My palms were sweating.

I was the one “in command”—but deep down, I knew:

This land would not be commanded.

Quietly, from beneath the passenger seat, I retrieved a small book I always carried with me—my prayer and chanting book from the Larung Gar Buddhist Academy in Sertar, where I had once studied.

I flipped to the pages already marked and began chanting softly, under my breath:

- The Vajra Armor Protection Mantra

- The Hundred-Syllable Mantra

- The Vajrasattva Mantra

- The Medicine Buddha Mantra

I didn’t chant to impress anyone.

I didn’t chant to show off my faith.

I simply hoped that our journey would be protected—not for our sake,

but for the people we were still trying to reach.

When Compassion and Common Sense Arrive Before Command

On the road to Anchang Middle School, we began to notice a problem—

a quiet imbalance in the distribution of aid.

Most supplies were being sent straight to the epicenter or to major cities officially marked as “severely affected zones.” But as we got closer, we realized: many of those areas had already been cleared out. Either the residents had been evacuated, or they were buried under rubble—unable to access the aid meant for them.

What those places needed now were heavy machinery and professional rescue teams—

not instant noodles, bottled water, or blankets.

Meanwhile, the villages and townships along the way, places too small to be noticed on a map, too remote to appear in media reports—had suffered just as much. Houses had collapsed. Food had run out. Nights were bitter cold. But these places had become aid blind spots.

We may have been among the first teams to notice this.

Perhaps because we weren’t following the “official mission route.”

We had come in trucks with bicycle from Chengdu.

Closer to the ground. Closer to people.

We were watching not the news—but the road.

So somewhere along the way, we made a decision:

We didn’t wait for permission.

We started handing supplies out on the spot.

The bottled water, the biscuits, the warm clothing, the simple tents we had carried from Chengdu—

we began unloading them, piece by piece, and placing them directly into the hands of cold, hungry villagers by the roadside.

There were no interviews by journalists.

No cameras rolling over them by camera men.

Just hands reaching out.

Just voices saying, “Thank you.”

Just us saying, “Take your time. No need to rush.”

That feeling—of placing relief into someone’s palms—was more real than any slogan.

We weren’t sure if it was by-the-book.

But we were certain:

It was the right thing to do.

Anchang Middle School

We finally arrived at Anchang Middle School, in the old township west of Mianyang.

It had become the main transfer hub for displaced people across the western earthquake zone.

No matter where you had fled from nearby, your journey would pause here first—

before being assigned a bus, truck, or any available vehicle heading toward shelter in Mianyang, Deyang, or Chengdu.

This place never stopped.

Even in the dead of night, there were people waiting—anxious, exhausted, yet alive.

Nurses sat under dim lights, quietly registering names.

Volunteers walked between rows of bedding, carrying water bottles.

People were afraid. But they were still breathing.

I still remember that night vividly.

There, in the open schoolyard, a hospital flag flapped in the wind—marked Zhongshan Hospital.

It belonged to a medical volunteer team that had come from afar.

They moved swiftly under the floodlights, weaving between people and supplies.

Not far from them, on two patches of earth, rose two silent hills:

One was a mountain of aid—blankets, food, bottled water, packed high and brightly colored.

The other… was a pile of bodies, awaiting transfer.

That night, I stayed inside the off-road vehicle with Zhang Yi.

The other three brothers curled up outside, beside the car, trying to keep warm under the open sky.

Mosquitoes came in waves, relentless.

Someone joked,

“Even the mosquitoes seem to be fleeing the quake with us.”

But no one complained.

Because we all knew:

To be here, lying under the stars, cold but alive—was already a kind of fortune.

Toilet Terror at 5 A.M.

Earthquakes, as it turns out, can mess with magnetic fields. I’m not sure if that interfered with my biological clock, but I can say for certain—it completely ruined my bowel schedule.

Before dawn, sometime around five in the morning, my stomach began to stir ominously.

I opened my eyes and realized my feet were swollen like two over-proofed lumps of dough—pushing at the seams of my shoes.

Standing up felt like stepping on a cactus.

No exaggeration.

After spending the night half-crumpled in a car seat, my blood circulation had basically gone on strike.

I hobbled over to a toilet beside the school building. Pants down, squat in place—finally, the first glorious segment had emerged—

and then, BOOM.

The earth began to shake again. Obviously, the BOOM is not my poop.

It was an aftershock.

No. A violent one.

Now… how to describe what I felt in that moment?

Honestly?

There was no time for feelings.

Just one primal thought screaming in my head:

“Aftershocks are supposed to get weaker… Right?

The toilet didn’t collapse last time, so it’s probably safe now… right???”

I forced myself to stay calm.

To stay put.

I clenched my jaw and carried on… but internally, I was spiraling.

All I could imagine was a brick dislodging from above and crashing straight onto my skull.

Or worse:

dying mid-defecation, face-down in a latrine pit.

That’s not just tragic—that’s reputation-ruining.

And then came the terrible dilemma:

Do I… clench and run?

But that would mean stumbling out bare-assed into an earthquake.

Absolutely not.

And then…

Out of nowhere, my mother’s voice echoed in my head:

“If it’s a blessing, don’t fear it.

If it’s a curse—you can’t escape it.”

Fair enough, Ma.

No escaping it. I shut my eyes. Tensed my fists. Grit my teeth.

And grunted my way to the end of that toilet session like a true survivor.

Wiped, pulled up my pants, stepped through a fine drizzle of falling dust—

and casually strolled back toward the car.

As if nothing had happened.

Of course, my teammates were halfway to a panic attack.

Apparently, someone had shouted:

“Brother Wu is missing!” (Yes, that’s me. In China, Chinese friends call me Brother Wu)

When I reappeared, I simply said,

“It’s okay. I’m fine. Don’t panic.”

Everyone let out a collective breath.

The world, for a moment, was calm again.

Joining Forces with the Red Cross

By the time we arrived at Anchang Middle School, night had already fallen. The lights in the courtyard flickered on and off, casting long, uncertain shadows. The whole scene felt chaotic—crowds of people, scattered information, piles of supplies stacked in corners—yet strangely, no one seemed to know who was in charge.

We couldn’t find a liaison from the Sichuan Red Cross. So, we settled down at the edge of the site, doing our best not to disrupt the existing operations. Everyone was exhausted. After an entire day of shaking ground, fractured roads, and frayed nerves, the body begins to give in.

But deep down, we knew—the real work hadn’t even started.

It wasn’t until the infamous “Toilet Incident” (a story for another page) that I realized—we couldn’t just wait anymore. I started asking around, searching for someone who looked like they were actually running the scene.

Between the school building and the playground, I noticed a woman—not tall, moving quickly, speaking firmly with furrowed brows and sharp focus. She barked out instructions while walking, clearly trying to stay ahead of the chaos. She didn’t have the look of a first-time volunteer. Despite the weariness in her voice and the tension in her gestures, she exuded something rare in a disaster zone: authority.

I asked someone nearby.

“Yes, that’s her. That’s Wang Ying—the coordinator here.”

She was completely drained.

Trucks, crowds, shouting, documents, confusion—everything was coming at her at once. There was no time to check who we were, whether we had credentials or background.

Our first interaction didn’t happen at a desk or in any formal setting.

It happened while jogging behind her, trying to squeeze in our entire story between her rapid strides.

I caught a moment as she paused to switch tasks. I got straight to the point:

“We’re a volunteer team from Chengdu.

Most of us are cyclists and mountaineers.

Some of us are certified first responders.”

She didn’t even have time to respond.

At that moment, someone shouted from across the lot:

“Sister Wang! We’ve got a truck of bottled water, but no one to unload it!”

Without missing a beat, she yelled back:

“Have this group do it!”

And just like that, our 20-person team was thrown onto the front line.

Over 1,000 crates of bottled water—we formed a human chain, passing them one by one from the truck to the distribution zone.

Just as we were finishing, another voice rang out:

“Wait, wait! This batch needs to go to the other shelter—they took too much!”

So, we turned right around and carried several hundred crates back onto the truck.

Honestly?

I was a bit pissed.

We came with good intentions, got thrown into hard labor, then had to do the same work in reverse.

But what could we say? We were fast, we were many, and we knew how to work together.

Within fifteen minutes—done again.

We dropped where we stood.

Some crouched down to smoke, others leaned against the wall with their eyes shut.

Then Wang Ying walked by again.

She saw us and, without hesitation, raised her voice:

“You guys are over here smoking?! We’re dying over there and you’re just hanging around?! MOVE!”

I’ll admit it—I felt a little wronged.

But I understood.

This was the disaster zone.

The pace was brutal. Resources were limited.

Nerves were stretched to breaking.

No one had the time or mental space to figure out who had just arrived, who had already done what, or who just moved 1,000 crates of water ten minutes ago.

She didn’t know that we weren’t really slacking off.

We were just waiting—after finishing one task,

for the next one to come.

In a disaster, collaboration rarely starts out clean.

There are no name tags, no org charts, no smooth handshakes.

You begin by showing up.

Then you carry the weight.

Then you wait for trust to catch up.

Wufu Village: From Volunteer to Rubble-Scavenger

To be honest, by the time we reached Wufu Village, I’d already swallowed a few lumps of frustration.

From being ordered to load, unload, and reload supplies like some kind of cargo yo-yo, to being scolded for “slacking” right after hauling 1,000 crates of water—all of us “rookie volunteers” were carrying a bit of emotional baggage.

But this was the disaster zone. There was no space for emotional management.

Every person here was being pushed forward by their emotions, not leading them.

So I told myself: Hold it in. There’s more work ahead.

Not long after, we were reassigned—sent with another group toward the direction of Qianfo Mountain Town, and eventually posted to a makeshift emergency station in Wufu Village.

But let me be clear:

This so-called “emergency station” didn’t look anything like what you’d imagine.

There were no medical tents, no Red Cross logos, no rows of medicine neatly stacked behind counters.

Nope. Our base camp was rubble.

Collapsed brick walls, cracked timber beams, shattered roof tiles…

Among this shattered landscape, we found a relatively safe, stable patch of earth and called it home.

There were no questions about where we’d sleep.

No one asked whether we’d eaten.

No registrations.

No name lists.

No subsidies.

Just the same unspoken understanding:

“You want to eat? Figure it out.”

Someone said the Red Cross was distributing food… but only if you had their official volunteer badge hanging on your chest.

No badge?

Then even if your legs gave out, your lips cracked from thirst—you’d be left to fend for yourself.

Thankfully, our team wasn’t built on resumes or uniforms.

We were cyclists, mountaineers, wild-campers—

the kind of people who thrived off the beaten path.

We knew how to carry, how to cook, how to improvise.

We had duct tape, headlamps, and grit.

If you can ride 500 kilometers through wilderness, a pile of rubble isn’t going to break you.

That evening, as night fell, we scavenged a few intact plastic stools from the ruins.

Against a crumbled wall, we stacked bricks into a stove.

The pot was borrowed.

The water was bartered from a local.

The firewood? Broken roof beams and scattered planks.

We threw everything vaguely edible into one pot:

A few packs of flattened instant noodles, plus a chunk of preserved pork that a villager had dug out from what used to be their kitchen.

When the pot started to boil, and the scent of salty broth filled the air, none of us spoke. It was the first hot meal we’d had in three days. So good it nearly brought tears to our eyes. Too salty. Meat too tough. Water barely enough. Fire uneven. But no one complained.

That meal tasted like a celebration—a quiet, smoky, carb-heavy celebration of the fact that

We were still alive. The team was still intact. We still had breath in our lungs.

One of the brothers grinned,

“This is the best damn meal we’ve had since entering Beichuan.”

I cracked a smile and added,

“Every James Bond movie starts with either an explosion or a sex scene.

Ours starts with instant noodles in a rubble pit — a sneak peek of the apocalypse edition.”

We leaned against the broken wall, gnawing at pork, slurping noodles.

In front of us were the darkening hills.

Far off, we heard a distant rumble—probably another collapse.

But right there, in that moment, we weren’t anxious anymore.

For the first time, we felt present.

Not heroic.

Not glorious.

Not part of anyone’s headline.

But real.

We were actually here, doing actual things, in the most human way possible:

Survive.

Share a meal.

And keep going.

May 15 – Mission to Qianfo Town: Assisting Evacuation and Monitoring a Quake-Dammed Lake

On the morning of May 15, Wang Ying from the Red Cross gathered our group along with several other volunteer teams and briefed us on the day’s assignment:

We were to head to Qianfo Town and carry out a dual-purpose mission—to help evacuate villagers with limited mobility, and to provide on-the-spot first aid to minor injuries we encountered along the route.

The road ahead was not an easy one.

Reaching Qianfo required crossing over mountain terrain, as the original canyon road leading to the town had collapsed in the earthquake.

Landslides and the formation of a quake-dammed lake (a temporary lake created when falling debris blocks a river) had completely cut off several sections of the route.

A local militia-led rescue unit had already entered the area and begun relief work. However, they were under-equipped to deal with injured civilians, especially those needing urgent but non-hospital care.

That’s where we came in—our team would act as a mobile first-aid unit, hiking into the disaster zone to assist with both evacuation and medical triage.

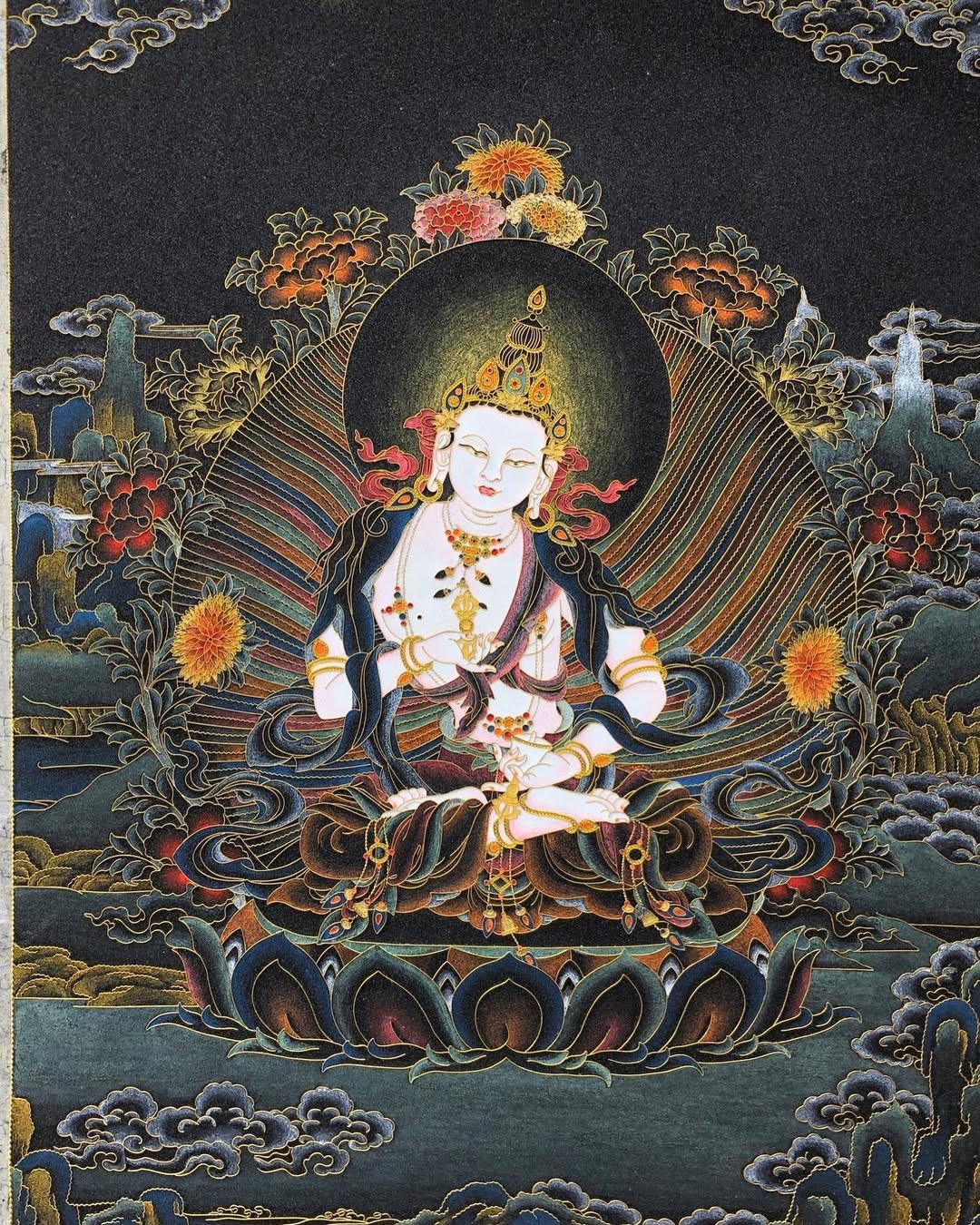

Qianfo Town – Land of Stone Buddhas, Shadowed by a Watery Threat

Qianfo Town, literally “Thousand Buddha Town,” is an ancient settlement named after the countless Buddhist statues carved into its surrounding cliffs. These figures—some serene, some solemn, some bearing gentle compassion—were painstakingly chiseled by generations of stone craftsmen. For centuries, they stood as silent witnesses to the region’s deep spiritual heritage and artisan legacy.

But the earthquake changed everything.

The quake triggered a natural damming of the valley river that runs through the town. A landslide had blocked the water’s path, creating an unstable quake-dammed lake. As the water continued to rise—fed by both rainfall and further slope collapses—the pressure on the fragile earthen dam intensified. Experts warned: if the barrier were to burst, the consequences downstream could be catastrophic.

Wufu Village, where our team was currently stationed, sat directly in the projected path of such a flood.

So this mission wasn’t just about humanitarian rescue—it was also about geological risk mitigation.

Saving people, yes.

But also, potentially avoiding an entire region from secondary disaster.

Jean Bottazzi: A Watchman with a French Accent and a Geologist’s Instinct

Our point of contact for monitoring the quake-dammed lake was a speleologist from France: Jean Bottazzi.

Jean had spent years living in Guizhou Province, and his understanding of the geological patterns in Southwest China was both deep and practical.

He spoke English with what I can only describe as a “foie gras-flavored” accent—and I replied with my “Sichuan pepper-infused” English.

Somehow, that linguistic oddity became the foundation for a unique rhythm of communication.

He spoke the language of rocks.

I translated it into the language of human risk.

Jean had an almost supernatural level of stamina.

Twice a day, he would hike deep into the observation zones near the lake, assessing water levels, dam pressure, slope fissures, and soil saturation.

He would return each time with short, sharp, and perfectly timed updates, letting us know whether the camp needed to prepare for potential evacuation.

He was our unofficial early warning system—not with sirens or satellites, but with boots, intuition, and a battered notebook full of sketch maps and handwritten calculations.

Marching with the Jinzhong Firefighters

For this operation, we were merged into a joint rescue team alongside a unit of firefighters from Jinzhong, Shanxi Province.

Most of them were barely out of their teens—some just 18 years old, with faces still carrying the gentle awkwardness of adolescence.

But on their backs, they wore heavy fireproof suits, and at their waists swung axes, ropes, carabiners, and emergency pouches.

Watching them climb the rocky mountain path, each step like hauling their own house uphill, I felt tired just looking at them.

They took point—clearing the path and rigging up safety ropes across unstable sections.

We followed behind, focused on tending to the injured, offering water, and comforting villagers shaken by what they had just survived.

Since the main road to Qianfo Town had been swallowed by the quake-dammed lake, we had no choice but to detour—scaling a steeper trail over the mountain, circling around to approach the town from behind.

Along the way, we encountered villagers evacuating on foot.

Some carried pots and pans, others led goats, and many had children clinging to their backs or arms.

Their eyes didn’t show panic or protest.

Instead, there was a kind of exhausted numbness, tinged with a faint shimmer of hope—the quiet, unmistakable recognition that

someone had come.

We moved through the mountains, stopping to dress wounds, offer water to the elderly, carry backpacks for children, and support those with twisted ankles or bruised ribs as they stumbled downhill.

The path was uneven—crushed stone and loose earth left behind by landslides.

Each step was careful, calculated. The destination—Qianfo Town, home to its thousand stone Buddhas—lay ahead.

But what mattered more was not just where we were going,

but what we were bringing with us:

a bit of order,

a bit of warmth,

to a road that had known only fear.

People Who Left a Lasting Impression on Me

The First Man: The Old Villager with a Nail in His Shoulder

He was the first person I met on that mountain road who left a mark I’ll never forget.

We were slowly making our way along a steep, makeshift trail carved into the hillside when we heard the clatter of loose rocks up ahead. Looking up, we saw an elderly man descending carefully. His steps were steady but strained. He had a large backpack, not strapped to both shoulders like you’d expect, but slung awkwardly over one side.

It looked uncomfortable.

As we stepped aside to let him pass, we sat down to rest and figured we’d offer help when he got closer.

When he approached, we asked,

“Sir, wouldn’t it be easier if you wore the pack on both shoulders?”

His face was dripping with sweat, but his tone remained calm.

“I can’t. There’s a nail stuck in my collarbone.”

We froze.

He lifted his shirt and pointed just beneath his collarbone.

What we saw wasn’t a cut or a scrape—It was a penetrating wound.

The head of a nail was visibly lodged deep into the bone.

The surrounding skin was bruised, swollen, turning purple.

He explained:

On the day of the earthquake, he had rushed home to save a few treasured items—not gold, not valuables, but old family belongings.

Just as he packed them, the house began to collapse.

A roof beam came crashing down on him.

By sheer luck, some debris beneath it cushioned the blow enough to keep him from being crushed.

But one nail—just a regular nail used for hanging things—pierced straight into him. He cried for help.

A neighbor came and used pliers to snip off the nail, leaving the bottom half embedded inside his body.

By the time he finished his story, we were speechless.

This wasn’t a scene from a disaster movie—This was real life:

An elderly villager, trekking a mountain path with a metal shard inside his collarbone, simply trying to escape with his life.

We didn’t have surgical tools.

All we could do was treat it like a puncture wound—Clean the area carefully, and use gauze and bandages to immobilize the nail, making sure it wouldn’t shift or worsen with movement.

As we worked, we kept repeating:

“There’s a Red Cross checkpoint down the road.

You must ask them to take you to a hospital.

You’ll need a tetanus shot, and that nail needs to come out as soon as possible.”

The old man nodded, his deeply lined face folding into a grateful smile.

“Thank you, thank you…”

We thought he’d slow down after the bandage.

Instead, he heaved the pack back onto his shoulder, turned, and charged forward down the trail—

chasing after the group of villagers who had gone ahead.

One of us joked,

“Did we just wrap him with a speed booster?”

But deep down, we all understood:

It wasn’t the gauze that kept him going.

It was his will.

I must not fall behind.

I must get out of here—alive.

In that moment, we realized something about survival: It doesn’t just belong to the uninjured.

It belongs to those who, even after they’ve been hurt, still choose to put one foot in front of the other—and keep walking.

The Second: The Little Girl with the Toy Bear

We were climbing a rugged trail, one cautious step at a time, preparing to meet villagers who might be coming out from the ruins ahead.

That’s when we saw her.

From around the bend came a small figure, running with soft, steady footsteps—a little girl, no more than seven or eight, with a stuffed bear strapped to her back.

She wasn’t carrying anything else.

Just that bear—dirty, frayed, its fur matted and curling—a silent witness to the long road she had already traveled.

Her hair was tousled, her cheeks smudged with dust,

but her eyes—her eyes were clear and bright, like mountain spring water.

The adults along the path couldn’t help but stop and look.

Heads lifted. Faces cracked faint smiles. Not the kind you give to something cute-but the kind that comes when, in the middle of ruin and rubble, you stumble upon a fragment of a fairy tale still breathing.

She reached where I stood.

I instinctively called out:

“Hey sweetheart, where are your parents?”

Breathing heavily, she answered:

“My mom and dad… they’re still digging.

They told me to go on ahead with the others.

We’ll meet up later, they said.”

Something clenched inside me.

“Do you know where you’re supposed to meet them?”

“Did they tell you exactly where?”

She paused, fiddling with one of the bear’s ears. Her lips tightened in a shy frown.

“Umm… I don’t think… they said.”

I knelt down to her eye level, softening my tone.

“Okay. Listen carefully.

When you reach the front checkpoint, find someone from the Red Cross.

Tell them your parents’ names, and if you know it, their phone number, okay?”

She nodded, gave a bashful little smile, waved, and continued running down the mountain with her bear bouncing along behind her.

Her pace wasn’t fast.

But her back was straight.

Her steps—stumbling, uncertain, but steady—looked as though she was walking the line between ruins and a bedtime story.

I stood there, watching her figure grow smaller.

And my throat tightened.

I didn’t know what she had lived through in the quake.

I didn’t know if she would find her parents again, or if that promised reunion would ever happen.

But I’ll never forget that smile on her face.

The only child we saw that day who smiled while passing through the disaster zone.

Innocent, yes—but radiant.

Like a sliver of light rising from the wreckage,

guiding the rest of us forward.

The Third: The Girl with the Crushed Foot

We were just packing up, getting ready to continue our climb, when we spotted two figures approaching from a distance— an elderly man, and beside him, a young girl, limping heavily.

But to our surprise, it was she who was helping him walk.

At first, I thought she was just tired.

But as they came closer, I felt my breath catch in my throat.

Her right foot was…flattened.

I mean it—crushed nearly flat.

I muttered under my breath,

“Fuck…”

Her foot had been smashed by falling rocks.

The midfoot arch had collapsed into a twisted, unnatural shape.

The skin was torn open, the tissue underneath swollen and pale.

Redness had already spread up to her ankle.

The edges were turning a worrying purplish-blue—signs of infection and inflammation.

She wore a pair of military-issue rubber shoes, the front of one crudely cut away to make room for the injury.

The shoe could no longer support her foot,

so she dragged herself forward using her heel, one slow, scraping step at a time.

This wasn’t just painful—it was an open wound, one that needed immediate medical attention.

I called over one of the brothers.

We helped her sit down and started prepping our supplies.

She wouldn’t look at her foot.

Instead, she turned her head and fixed her gaze on the old man—

the same man she had been helping all this way.

We knew this was going to hurt.

Possibly more than when the injury happened.

Step one: disinfection.

We took turns rinsing the wound with alcohol and hydrogen peroxide.

As the alcohol touched raw tissue, she flinched hard, her brow wrinkled with pain—but not a single sound came from her mouth.

Then came debridement:

removing dirt and tiny stones lodged inside.

Every movement tugged at her nerves, and her face mirrored each motion—tightening, releasing—but she never cried.

She just clenched her jaw, turned her head to the side, and kept one hand firmly wrapped around the old man’s arm.

I was stunned.

Here she was—probably no older than fifteen—her foot half-destroyed, and she was still the one doing the holding.

We wrapped her injury in sterile gauze, a few layers, creating a barrier to prevent further contamination, as well as making sure the wound can breathe.

We urged her to rest a while.

She politely declined.

“There are others ahead,” she said quietly,

“who might need more help than me.”

She nodded to us, thanked us, then stood up, braced the old man again, and began hobbling downhill—step by limping step.

She never asked for help. She didn’t ask to be carried. She didn’t cry, or complain, or linger.

Her gait was crooked, painful. But there were no slogans, no drama.

Only one raw, instinctive thing:

Responsibility.

Even in pain—she refused to stop caring for someone else.

The Fourth: A Mother, Her Baby, and a Father Caught in Between

That afternoon, on our way back to the rescue checkpoint where we started in the morning, we saw a man slowly approaching from the back direction.

He was carrying a small backpack, his steps labored, his expression blank. When he reached us, he said nothing. He just sat down heavily on a roadside rock, panting, silently resting.

Then he looked up the hillside behind him and said,

“Please watch this bag for a moment.”

And with that, he turned and ran back up the slope.

A few minutes later, he returned, this time supporting a woman in a sweater which could a little bit too warm for the weather, who clutched a newborn baby tightly against her chest.

The baby was so small—barely a breath of life—wrapped in a blanket, his eyes still fused shut, his body curled, head nestled beneath the mother’s chin.

We quickly learned the child had been born just three days earlier, on May 10th. It was a near-natural delivery, as it is common practice to ease childbirth, the doctors had performed an episiotomy—a clean incision to assist delivery.

The wound hadn’t yet healed. The stitches were still fresh.

And then—the earthquake hit.

This family of three—husband, wife, and newborn—barely made it out of the hospital alive. The man dragged his wife out. She held the baby in her arms.

Seconds later, the entire hospital collapsed behind them.

They went home hoping to gather a few things—only to find their home no longer existed.

Not collapsed—erased. All in rubble remained.

All they had now was that small backpack, holding everything they owned, not even the baby’s birth certificate.

The mother was weak, her wound still bleeding, yet they had joined the stream of evacuees.

But they were too slow. The crowd moved on, and they were left behind.

We walked with them.

When the baby got hungry, the mother sat down on a rock,

lifted her gown, and let the child feed.

Her face was tight with pain,

but her hand gently tapped the baby’s back—as if the world had paused just for that moment.

She didn’t cry. She didn’t speak.

Her face showed no expression—only the hollow, focused look of someone who had long since passed her limit but kept going anyway.

As dusk fell and the distant outline of a Red Cross tent came into view,

the mother suddenly picked up her pace.

She walked faster, as if some final reserve of strength had flared within her.

The baby still in her arms, she rushed forward toward the shelter.

We followed, jogging.

The husband was trailing behind.

She reached the aid station, handed her baby to a nurse—and collapsed.

Just like that—her body folded and slid to the ground.

Not a sound.

Not a scream.

The father, still meters away, saw her fall and sprinted without a word.

We checked her immediately.

Airway clear.

Heart weak but beating.

Pupils reactive.

Skin cold and pale.

It was exhaustion-induced shock: extreme fatigue, blood loss, and dehydration.

We elevated her limbs, gave her salt-sugar water, tapped her cheeks gently.

A few minutes later, she stirred.

Her eyes opened slowly. She didn’t ask where she was. She didn’t ask if she was okay.

Her first words were:

“Where’s my baby?”

Not “Am I alright?” Not “What happened?”

Only that.

Where is my child? Is he safe? Is he crying?

At that moment, I stared at the dust beneath my boots and felt something in my chest collapse in silence.

I’ve thought about her many times since. How did she make it?

A woman who had given birth just three days before, with unhealed wounds, contracting abdomen, bleeding, and barely nourished, still carried her baby across miles of broken earth—through aftershocks, hunger, sun, and silence.

Was it willpower? Instinct?

A mother’s unspoken, non-negotiable urge to protect?

Yes. All of it.

She hadn’t just reached her limit.

She had long since surpassed it.

And what carried her forward

wasn’t food, wasn’t strength, wasn’t fitness.

It was something with no calories, no protein, no vitamins, but strong enough to push back against death itself.

That day I understood:

The body does not determine how far a person can go.

What does, is whether there’s still a reason not to stop.

Collapse does not begin in the limbs—

it begins in the heart.

And this mother, never collapsed.

Seventeen Years?

For me, this isn’t just an anniversary.

It’s not the start of a memoir, either.

This—what you’re reading now—is a part of my life, woven deep into the marrow, impossible to extract.

Two things prompted me to start writing this piece today.

On May 11, 2025, an American friend asked me after reading my story about How I fought with PTSD on www.chemsterdam.com:

“How do you live with PTSD?”

She saw the alcohol drinks and the bicycle in my life—but what he wanted to understand was the thread connecting them.

It was a vast question, and I realised: to answer it, I’d have to begin with the moment that changed my life.

One of them, at least.

(My friend and I had a coffee in Haarlem after church service on Sunday, 11th, May, 2025)

The next day, May 12, happened to be the anniversary of the Sichuan Earthquake—Seventeen years have passed.

And still, some images remain vivid the moment I close my eyes.

So I sat down and began to write.

At first, I intended it as a short version, the kind of retelling I’d offer to someone like Stephanie—just the basics, just enough.

But once I began, the memories started turning like wind-blown pages, each one rising on its own gust, pulling the next with it.

Details I hadn’t thought about in years came roaring back.

What I thought would be a brief reflection, turned into more than 20,000 characters in Chinese.

I revised, trimmed, rearranged—and eventually, it became the version you’re reading now. I did skip a lot of details and focused on the things I really want to share, maybe in future I could add more to this page.

This Is Not Just Remembrance

I didn’t write this just to commemorate a date on the calendar.

I wrote it because, as someone who lived through it, I know I carry a unique perspective—and that perspective might matter to someone.

First, I hope that those who have never heard of this disaster might come to realize: there is suffering in this world that you cannot imagine.

And within that suffering—some struggle, some vanish, and some are left behind.

If you’re still here, still breathing in this very moment, then I urge you:

cherish the peace you have, and the grace you’ve been given.

Second, I hope that those who have ever tried to understand me might finally see:

I am not a “simple person”, as everyone is more complicated that you think, not someone you can summarize in a sentence or define by a profession.

One friend once told me,

“Your complexity borders on the unreal.”

But after hearing these stories, she fell silent for a long while, and then said:

“You are not only real—you make a lot of sense now.”

But let me be clear:

I didn’t share these stories to become “worthy of respect.”

What I hope, is that this so-called respectability would lead to a deeper question:

“If Hans doesn’t deserve it—then where does his grace come from?”

My answer is simple:

Grace has never been about deserving.

I am alive today not because I am stronger than others, but because the Lord—He knows my task is unfinished.

And so, He continues to give me my daily bread. He allows me to taste peace in suffering, and find joy in the dark.

🔒 The content below is available to subscribers only 🔒

In the following section, I share my reflections on TULIP—a theological framework that has shaped how I see grace, suffering, and calling.

This is not for everyone, but for those who are curious about my faith and want to understand what sustains me beneath the surface.

If you decide to subscribe or support this work,

please know:

I hope it comes not out of obligation, but from a cheerful heart.

And truly—if you’ve read this far, you’re already walking alongside me.

Thank you for being here.

Suffering and Sovereign Grace: A Calvinist Reflection on the 2008 Earthquake

As someone born and raised in China, I once clung to a simple yet deeply rooted belief:

"Good is rewarded; evil is punished."

This moral formula was handed down from generations past, embedded in proverbs and daily speech. But on May 12, 2008, that conviction began to crack. The Wenchuan Earthquake claimed nearly 70,000 lives. Among them were parents, children, volunteers, teachers, workers. Was it justice? Were they all evil?

The mother who collapsed at the Red Cross tent after walking days with a newborn in her arms.

The grandfather descending the mountain on foot, a nail embedded in his collarbone.

The girl with a crushed foot who still helped an elder escape.

The child who ran with a torn teddy bear and a smile.

These were not villains. These were human beings—caught in a moment where morality seemed irrelevant and suffering fell like rain.

And I began to ask: If morality can't shield us from tragedy, what does that say about the architecture of grace?

I. Human Limitations

After the earthquake, one truth stood clear: wanting to live doesn’t mean one will survive. That choice is not ours.

"No one knows when their hour will come. As fish are caught in a cruel net, or birds are taken in a snare, so people are trapped by evil times that fall unexpectedly upon them." —Ecclesiastes 9:12

We do not choose our birth. We cannot schedule our death. The idea that “my fate is mine alone” is a beautiful illusion. In truth, our so-called free will often only briefly overlaps with God’s sovereign decree.

We do not survive disaster by effort. Nor do we escape judgment by merit. And when we judge others—comparing sins, weighing worth—we forget that none of us stands righteous.

"Who can say, 'I have kept my heart pure; I am clean and without sin'?" —Proverbs 20:9

II. Grace, Not Works: Unconditional Election

Were some of the dead "better" than the living? Yes.

Were some of the living also guilty? Absolutely—including us.

"There is no one righteous, not even one." —Romans 3:10

"If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us." —1 John 1:8

No amount of good behavior can cancel catastrophe. The earthquake did not sort the righteous from the wicked. It unveiled the frailty of works-based hope.

We cannot earn survival. We cannot earn salvation. It is grace, not merit, that saves.

III. Who Lives, Who Dies: Limited Atonement & Irresistible Grace

In the aftermath, I witnessed what many called miracles:

- A man pulled alive after 72 hours under rubble.

- A woman who stepped outside seconds before a collapse.

- Another who died just inches away.

Why did some live and others perish?

Not because of behavior. Not intelligence. Not even faith.

"I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion." —Romans 9:15

Election is not transactional. It is mysterious and sovereign. It is not a cruelty; it is a mystery that leads us into worship.

A Note on Being Chosen

We were not chosen because we were good. We are not loved because we are lovable.

We are chosen because He is merciful. We are loved because He is love.

This truth does not make us arrogant—it humbles us. And in that humility, we desire to obey—not to earn love, but to respond to it.

Knowing this, we do not judge others. We assume the best. We remember:

They too are trying, imperfectly, to follow the Lord they know.

This is not cheap grace. This is grace that softens judgment into compassion and pride into gratitude.

IV. Who Endures: Perseverance of the Saints

I saw resilience I cannot forget.

- The mother, bleeding and dizzy, who reached the tent before collapsing.

- The teenage girl with a ruined foot, helping an elder.

- The volunteers, hollow-eyed and sleepless, yet still moving.

Was this willpower?

Partly.

But beneath that willpower was grace—unseen, but strong as bedrock.

"The Lord will watch over your coming and going both now and forevermore." —Psalm 121:8

That mother didn’t faint when she reached her limit. She had passed her limit long before.

She was sustained by something deeper than adrenaline. She was carried by grace, disguised as maternal instinct.

Witness of the Cross

I witnessed the collapse of flesh—and the perseverance of the soul.

I saw moral frameworks fail—and the cross remain.

I saw that suffering does not contradict God’s love; it reveals the necessity of grace.

So today I testify:

We are limited.

We are broken.

We are not our own redeemers.

And yet—we are loved.

Not because we chose Him, but because He chose us.

"You did not choose me, but I chose you." —John 15:16

And with Jesus and a bicycle, I am still here—still riding, still healing, still held by sovereign grace. PTSD is still there but not dare to approach me.

Thank you for reading.